For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known (1 Corinthians 13:12).

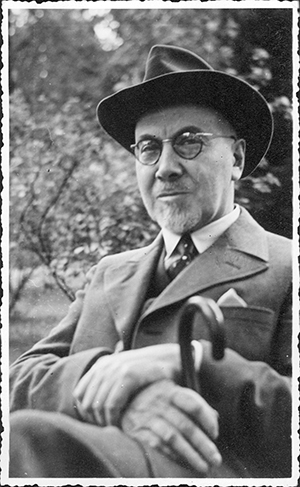

PHOTO COURTESY OF HEIDI NEUMARK

Heidi Neumark’s grandfather, Moritz Neumark, who died in a concentration camp.

Just after midnight, the ringing cellphone beside my bed woke me up with a rush of adrenalin. I wondered who had died. Did I need to put on my clerics and head to a hospital? But no, this was our daughter, Ana, calling with news that I am still trying to absorb. Did I know that I was Jewish? Did I know that my grandfather died in a concentration camp? Did I know that my grandmother was a death-camp survivor?

What I knew is that my grandfather Moritz died of a heart attack before I was born. This is what my father told me when I asked what had happened to Opa. I knew my parents were lifelong Lutherans, and I’d served as a Lutheran pastor for nearly 30 years. When Ana said her information came from Wikipedia, I almost laughed. This was clearly a case of mistaken identity.

Sunday morning and multiple church services were fast approaching. I needed to sleep, but instead I went downstairs to find Ana sitting in bed with the computer propped on her lap. She had been up late Googling family names. When she hit on Moritz Neumark, a page opened the door into an alternate reality where Moritz had morphed into a child named Moses Lazarus.

I was sucked into a dizzying whirl of revelations as one website pulled me into another and then another.

Hours later, while it was still dark, I fell back into bed and lay wide-eyed on the sheets, disoriented and wrapped in sadness. How was it possible that I was never told the truth? I believed that I was especially close to my parents, their only child. I believed that they had passed on the faith they had inherited from their parents and their parents before them.

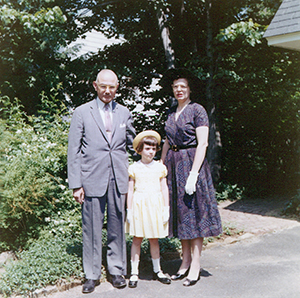

PHOTO COURTESY OF HEIDI NEUMARK

Neumark standing between her parents, Hans and Barbara.

My maternal grandparents met and fell in love as teenagers in a Lutheran youth group at their Brooklyn church. Admittedly, I was less clear about the courtship of my father’s parents, but they had raised my father and his two sisters as German Lutherans, or so I thought.

Bound for New York

I knew my father came to the U.S. from Germany in 1938. He had a doctorate in chemical engineering and his parents put him on a boat headed for New York to give him a better, more stable future than seemed possible in Germany at the time.

This made sense and was true, as far as it went, which turns out not to have been very far at all.

What I hadn’t known was that soon after my father landed here, my Jewish grandparents were deported to Theresienstadt, a concentration camp in what is now the Czech Republic. There my grandfather was murdered within a month and my grandmother slowly starved until her near miraculous rescue.

What does it mean that my faith has come to me not as I imagined — a cherished inheritance handed down from generation to generation — but through a trail of terror?

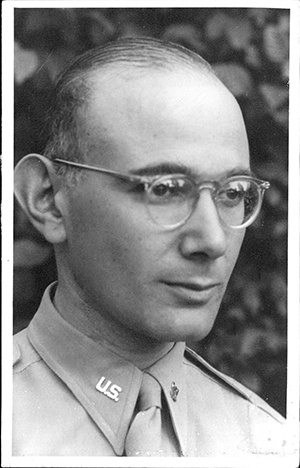

PHOTO COURTESY OF HEIDI NEUMARK

Neumark’s father, Hans.

Within months of my discovery, I began a journey that took me to Germany, the Czech Republic, Poland, Brazil and a Passover table in Los Angeles with some newfound second cousins. As I sat at that candlelit table, my wilderness journey continued with some things falling into place and much that remains unsettled and unsettling.

My entire ministry has included work for social justice — in South America, the South Bronx and now at a Manhattan church with a shelter for homeless lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender youth and undocumented immigrants. I’ve always been drawn to voices that others ignore. Now I see that the silenced cries of my murdered grandfather and other lost Jewish ancestors have reached out to me through the voices I can hear.

Hearing the echoes of history

I also hear other echoes of their history in the hate-speech used to demonize and dehumanize today. I feel much more viscerally sensitive and alert to anti-Semitism within and beyond the church. Silence is no option, and bearing witness to the story of my Ashkenazi Jewish forebears now feels like an urgent part of my calling.

After the sleepless night of my midnight discovery, it was time to pull myself together and show up at church. As the little ones ran up the stairs for “Wee Worship,” I realized that I wasn’t the only one in church that morning who is haunted by questions and longing to know more about my roots.

PHOTO COURTESY OF HEIDI NEUMARK

Hans with Neumark’s mother, Ida.

A little boy poking around in the basket of musical instruments is asking questions about the father who left before he was born. A preschooler clinging to her mother was adopted from the other side of the world where her birth mother left her carefully wrapped in a purple quilt on the side of the road. Three rambunctious little boys come in with their parent, who is fine with them calling her “Dad” even though she is now a woman.

I’m hardly alone in wresting with issues of identity. Throughout the morning I looked out on people of all ages filled with their own questions over things left unsaid and unexplained, aching to know more. I’ve been blessed to uncover much of my hidden inheritance, and yet for now we all see through a glass darkly and await the day when we will know as fully as we are known.

PHOTO COURTESY OF HEIDI NEUMARK

Neumark with her grandmother.