Reading today’s headlines, one might easily sense the gulf between faith and science widening. Polls show that many Americans feel science and religion are in conflict, and culture wars continue to rage around religious convictions and belief in science. But for Carmelo Santos-Rolón, it’s more important than ever that faith and science are in dialogue.

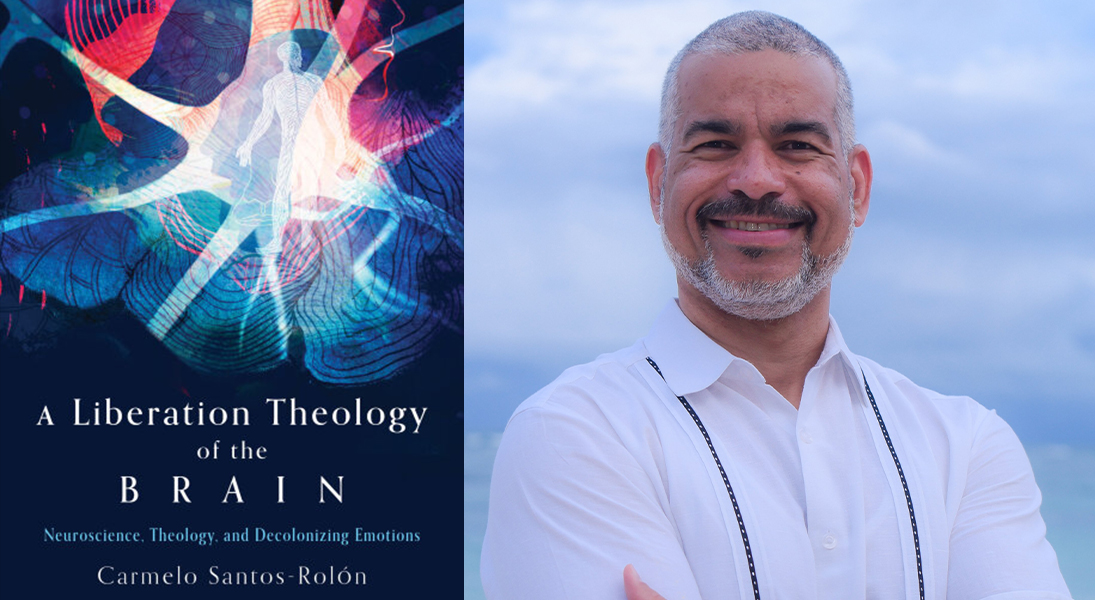

A scientist turned pastor, Santos-Rolón believes that science and theology can work together to reveal the beauty of God’s creation and bring healing to the world. In his new book, A Liberation Theology of the Brain: Neuroscience, Theology, and Decolonizing Emotions (Fortress Press, 2025), he connects the science of the brain, mind and body to the mystery of transcendence—and to liberating ourselves and others.

Over email, Living Lutheran interviewed Santos-Rolón, who serves as ELCA director for theological diversity and ecumenical and interreligious engagement—and earlier taught a course called “God and the Brain” at Georgetown University—about how his book guides readers to better understand how they might take action to dismantle oppressive personal and systemic structures.

Living Lutheran: How do you describe A Liberation Theology of the Brain to new readers?

Santos-Rolón: The book is a conversation between theology and neuroscience about the power of the word of God to decolonize our nervous system from patterns of emotions, behaviors and thinking that perpetuate oppression and systems of exclusion or marginalization.

Neuroscience allows us to explore what happens in our brains, bodies and minds—which are beautifully and inextricably one—when we are touched by the living word of God in the power of the Holy Spirit. Liberation theologies challenge us to remember that the salvation proclaimed in the gospel is a wholesome salvation, which includes pardon from our sins but also liberation from all forces that keep us apart from the fullness of life that God intends for all. Sometimes those demonic forces take the form of ideologies, biases and behaviors that live within our brains and nervous systems and result in the dehumanization of many, justifying cruelty and injustice.

A Liberation Theology of the Brain is an exploration of the dynamics underlying those processes by which our minds, brains and emotions become colonized by such devastating forces and how the church can become a matrix of healing and a force for wholesome liberation.

You reference recent developments in neuroscience that were important to how you synthesized the themes of the book. Could you tell readers a bit about them?

Two stand out. First was the very creative proposal of Patrick McNamara—author of The Neuroscience of Religious Experience—on how the purpose of religious experiences from a biological perspective seems to be the integration of our fragmented selves into a more cohesive, strong and unified self (at least when things go right). To my theological mind, that sounded very similar to what I had learned in my pneumatology research regarding the way the Spirit of God operates. So I couldn’t resist bringing those two insights together into conversation.

Science is a gift from God, not an adversary.

The second development in neuroscience that was key to my thinking was the finding by Lisa Feldman Barrett—author of How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain—that emotions are not premade on an immutable mold but rather made through the influence of language from our earliest years of infancy and continue to be shaped through adulthood. To my Lutheran mind, that reminded me of Martin Luther’s On the Freedom of a Christian, of how the way the soul of the believer is transformed by the word of God is similar to how the iron is transformed by the fire. There were many other influences, which I mention throughout the book, but those two were key.

Why do you believe science and religion need each other?

Science is a gift from God, not an adversary. Science is already present in the gifts of reason, curiosity and imagination with which God has endowed us. And it was there also in the Garden of Eden, in the responsibility given by God to the human creature to name all living things. That is, not to call them by arbitrary names as an exercise of egotistical power but instead to discover their true names, identity and nature, which is what science is about at its best: inquiring into the true nature of things.

But science, like anything else, is done by humans and not by angels, and therefore, because of human sin, it is capable of being distorted, misused and abused for other purposes than the thriving of all of God’s beautiful creation. So a healthy portion of the hermeneutics of suspicion developed by liberation and feminist theologians might be helpful for those engaged in science. That [theology asks,] what is the real driving force of this research? Profit? Power? Knowledge? Healing? Who benefits, and at the expense of whom? What perspectives and whose questions or problems are favored, and which ones are discarded or ignored?

Beyond that, theology also invites [scientists to recover their] awe at God’s creation. It invites the scientific gaze to get unfrozen and aim beyond the horizon toward the mystery of love, to which we all owe our being. To remember God. Not to bring religion or ideology into the practice of science but to recover the sense of awe and humility before the vastness of God’s awe-inspiring creation.

How you can your readers, in the ELCA and otherwise, better facilitate the kind of dialogue you call for between science and theology?

When I was in seminary at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago (LSTC), we had a class called “The Epic of Creation.” Every Monday evening, a scientist and a theologian would give a public lecture on a topic related to an aspect of creation and then have an honest conversation with each other and, afterward, with the participants over dinner. The focus of those conversations was not to push for a particular understanding but to actually listen carefully to what different perspectives and approaches have to say about a given question of great importance to all of us.

There is a deep connection between the mystery of transcendence and the work of dismantling oppressive structures.

We need more spaces like that in our colleges, congregations, camps, retirement communities and so on. Not only with scientists and theologians but also with historians, sociologists, economists and community organizers. Given the strong forces polarizing us these days, we especially need spaces where we can listen to voices that are being excluded or silenced. Imagine if all I knew about you was based on what people who didn’t like you very much were telling me about you! Would I have an accurate understanding of who you are and what you stand for?

We must seek opportunities to listen to each other directly. Dialogue, as I was taught at LSTC’s Zygon Center for Religion and Science, is not the same as debate; its goal is a clearer understanding of each other’s perspective, even when—especially when—we don’t agree. Furthermore, the goal is a richer understanding of the problems we’re trying to address, including their various dimensions. For example, the historical dimension, [asking,] how did we get here? What are the forces driving this situation? And so on.

How do you hope readers will engage with the book and take action after reading it?

I think there is a deep connection between the mystery of transcendence and the work of dismantling oppressive structures. … The truth is that whoever has had the experience of being in the presence of the mystery of God cannot help but to love, because God is love. And when I love my neighbor and I see them being hurt, exploited or pushed to the margins, love moves us to denounce and to dismantle whatever is harming them. Whether that’s governmental policies or unjust laws, prejudiced behaviors and attitudes (especially within ourselves) or apathy, we cannot help but roll up our sleeves and do our part to seek the well-being of our neighbors and siblings, especially those who are most vulnerable.

At the individual level, or at the level of communal spiritual practices, I love a phrase I learned from my first professor of spirituality many years ago: “Cultivate a spirituality of curiosity for the other.” That includes curiosity for those who hold opinions we find offensive and harmful. Is there any truth at the heart of their beliefs and behaviors, even if a distorted or misunderstood truth? From a different perspective, we must learn to enjoy and celebrate the rich diversity with which God has blessed us, and explore that diversity with a spirit of humility and curiosity. … We should approach each other with a sense of awe and the expectation to be surprised by God in the way we encounter each other.

I also emphasize in the book the importance of prayer. Not in a transactional way but by simply placing ourselves in the presence of God, with all our burdens, wounds, joys and dreams, and letting God be God. The experience is truly liberating and empowering.

Finally, we can create small spaces where we can practice living “otherwise.” In those spaces, we can begin to rehearse what it would be like to be already on the other side of the horizon of eternity, where heaven has come down to earth and all of God’s beloved creation has found its fullness.