At the U.S.-Mexico border south of San Diego, a multinational congregation walks on holy ground, sharing the eucharist every Sunday at the same time but in two different locations. This is the Border Church, divided by a 30-foot wall and, for the last five years, a few miles.

It wasn’t always this way, said Manuel Retamoza, pastor of the U.S. side since June and co-pastor of St. Andrew Lutheran Church in San Diego for 20 years.

Retamoza remembers taking his young children to worship at the border about a decade ago, when the Border Church met in Friendship Park. The park’s round, paved plaza rests on both U.S. and Mexican soil, split in half by a wall. In those early days, communion could be passed through a chained metal fence. Then a bigger wall was built with solid material so that nothing could be passed through it.

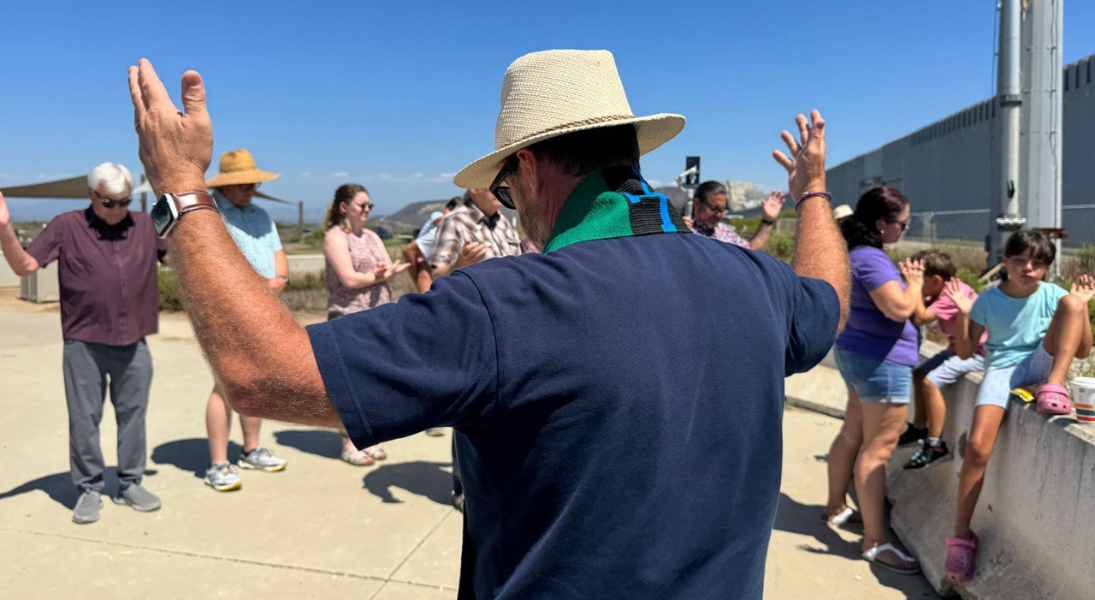

In 2020, the U.S. half of Friendship Park was closed to the public, and though worship continued in the Mexican half, worship in the U.S. moved about three miles away, to a site called Whiskey 8. The congregation now unites in prayer with a phone call at the beginning of worship. When the call ends, both sides continue to worship, separately but as one church, bound by the simple act of praying and eating together.

Retamoza’s father was born in Mexico and often took the family to Tijuana to visit relatives. Raised in Northern California, Retamoza traveled to Mexico with the youth group at his Baptist church on mission trips to build houses.

“I got tired of hearing from my peers, ‘all these poor Mexicans,’ but we’re not these poor Mexicans,” he said. The organizers of his mission trips gave him permission to show his friends a different Mexico that included both middle-class and affluent families. “I gave them a tour of my Tijuana. I took them to the market, to the mall and to my family’s home, which is bigger than most of our churches.”

He said he has felt a call to work along the border ever since. “Now, in my 50s, I’m finally working on the border,” he added.

The Border Church’s U.S. ministry extends beyond a common worship service to serve asylum-seekers or other immigrants who have been detained by the U.S. Border Patrol between the border wall and a secondary wall. The wall extends from Friendship Park to the coast and into the Pacific Ocean. Asylum-seekers are sometimes held for several days before they are taken to processing centers.

Retamoza said that along with hosting worship, the Whiskey 8 site also serves as a place where efforts are coordinated to get items—foil blankets, breakfast bars and food that can be heated with hot water—to those being detained between the walls. Sometimes the medics staffing Friendship Park come to the Border Church for supplies to treat those who have been injured while scaling the wall or who are sick, because the medics are allowed to use their supplies only for those in uniform who serve at the wall. “We often talk as pastors as being a ministry of presence,” he said.

“That’s what Border Church is. A ministry of presence. A ministry of experience.”

Maria Santa Cruz, assistant to the bishop for Latiné ministry in the Pacifica Synod, said accompaniment is central to the ministry of the Border Church and other synod congregations, especially as officers from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement seek out immigrants without complete documentation.

“We need to bring them the peace that they lost,” Santa Cruz said. “We’re living in a time like the first apostles, when Jesus was killed and people were in their homes in fear. Jesus first said, ‘Peace be with you,’ because they had no peace.”

The Border Church

The Border Church was launched in 2011 as an interdenominational ministry serving people at Friendship Park, which has been a gathering place since 1849. For generations there were no border barriers, which allowed people to mingle freely. In the decades that followed, various materials were used to mark the border, including rope, barbed wire and chain-link fence.

In 2006, the federal government used eminent domain to seize land from California and began to construct the first wall that divided Friendship Park. Beginning in 2011, border patrol officials opened the U.S. side of Friendship Park for limited hours each weekend, with only 25, then 10, people allowed in the park at one time.

Since 2020, Friendship Park has been closed, depriving people who live legally in the United States but lack the status to travel freely the chance to reunite with family in Mexico, to meet grandchildren for the first time or to say goodbye to dying loved ones.

The congregation operated at Friendship Park from late 2011 through February 2020, when the park was closed. While the church continues at Friendship Park in Mexico, the U.S. site shifted. “Despite our separation, the ministry of unity we offer stands as resistance to separating forces at our border,” the church has said.

Access to Friendship Park was restored in August; for the first time since 2020, cars are allowed to drive into the area close to the park.

Border Church ministers in an area where San Diego and Tijuana function as twin cities, with 70,000 people crossing from Mexico to the United States every day to work, shop, attend school and conduct business. “Some of my relatives, they drive the kids over every morning to drop [them] off to school because they’re well off enough to bring their kids to private school here,” , Retamoza said.

The church and its community stand as witnesses as larger border issues roil Southern California and other areas along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Living in fear

Santa Cruz said the ways the United States has enforced immigration laws since early 2025 has changed congregational life for some.

“Right now, the congregations with Latinos, they’re almost empty,” she said. “People aren’t attending because they are afraid.” In one congregation, attendance has dropped from 40 people to seven as immigrants stay home, afraid to shop or escort their children to school.

“People don’t have food or water because they’re afraid to come out of their houses,” Santa Cruz said. “So others are taking to them. This is what I told pastors. Our congregations need to help these people. We need to accompany them.

“We need to bring them the peace that they lost.”

She recalled being with a congregation member when the woman received a phone call from her daughter, who reported that the father had been detained while picking up his child from school. “The poor kid was crying and crying,” she said.

Her advice to church members is to “understand the situation and do not judge. Don’t ask, ‘Why don’t they have documents?’ ‘Why don’t they apply?’ I want them to understand the situation, the fear. They are human beings, children of God, and have gifts and talents to share. Accompany them in this time of fear.”

Retamoza said that along with accompaniment, he wants people to experience the separation created by border walls. “Come and experience the wall anywhere in the U.S.,” he said. “There are people willing to share that with groups and congregations.

“What I really want is justice. Justice would mean not having walls separating us from people, as a congregation, as families.”