Lectionary blog for May 22

The Holy Trinity – First Sunday after Pentecost

Proverbs 8:1-4, 22-31; Psalm 8;

Romans 5:1-5; John 16:12-25

About 20 years ago I served a church near Vanderbilt University. In good weather I often ate my lunch in a park near the campus. One day as I tore off pieces of my hamburger bun and threw them into a pond full of ducks, I noticed a dad and his 5-year-old sitting on a nearby bench. The dad had his head buried in books and papers on his knees while his son played nearby. Suddenly, junior got up and stood at Daddy’s knee and asked a question about the ducks or the sky or something. Without looking up from his papers, Dad answered with a long, rambling, compound sentence full of words and concepts far beyond the grasp of the average adult. The little boy looked at his father for a minute and then said, “Uh, Dad, are you talking to me?”

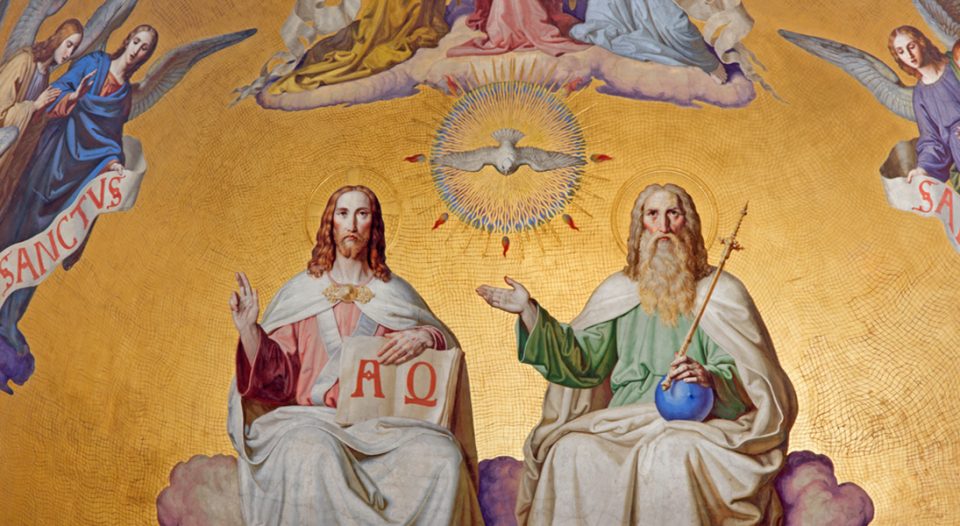

The Athanasian Creed is traditionally said on Trinity Sunday:

Uncreated is the Father, uncreated is the Son, uncreated is the Spirit. The Father is infinite; the Son is infinite; the Holy spirit is infinite. Eternal is the Father, eternal is the Son, eternal is the Spirit. Yet there are not three eternal beings, but one who is eternal; as there are not three uncreated and unlimited beings, but one who is uncreated and unlimited.

It goes on like that for a page and a half. “Uh, Dad, are you talking to me?”

The Trinity is a difficult subject to talk about and to preach about, mostly because if we try too hard to explain the inexplicable we always make a mess of it. By the time we have come up with an explanation that makes sense, we discover we have veered off track and said something that’s not actually true. We have a tendency to say things like: God is one and we experience the Holy in three different ways, or that the one God puts on three different faces (Father, Son and Holy Spirit) depending on our human need – like I’m one person but to my siblings I’m a brother and to my wife I’m a husband and to my children I’m a dad. Sounds good, but it misses the point.

As the Athanasian Creed makes exceedingly clear, paragraph after paragraph, there are three persons, separate yet united, all God and yet all one God. Turning that divine reality into something that fits a mathematical or logical model that is easy to grasp is simply not possible. In Corinthians, Paul reminds us that we are stewards of the mysteries of God. How God can be both three and one is a mystery of God – and I’m OK with that.

For, while I am not able to make complete sense of the life of God in the Trinity – the life of God in the Trinity makes sense of my life in the world. Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Creator, Redeemer, Sanctifier. Maker of heaven and earth, my Lord and Savior, the giver of life. All these names and phrases and descriptions swirl around in my head and let me know who God is and what God has done in the past and what God is doing now, in this place and in this time.

A number of years ago the Barna Research Group reported a study that asked a cross-section of Americans what one sentence or phrase was the most important they had ever heard.

- I love you.

- I forgive you.

- Dinner’s ready – let’s eat.

The Hebrew Scriptures are the long saga of God’s desire to love God’s people. If I had to sum up the meaning of everything from Genesis to Malachi, “God says I love you” would do nicely. God made the world and God loves the world. God made us and God loves us. God the Father, God the Creator, God the Maker is love. All the trees in the forest and the water in the oceans and the birds in the sky scream out to us, “God is love and God loves you, and you, and you. God loves all of us.”

But because God loves us, God made us free, made us free to make choices, free to live our lives. And free people often make bad choices, either through ignorance or from evil intent. Either way, it is a fact of human existence that we make a habit of messing up a good thing, and it is when we have realized our failure to be good that the mere knowledge that God loves us is simply not enough.

Why? Because paired with our knowledge of God’s love we now have an awareness of our unworthiness, our inability to be the good people we want to be, of our failure to live up to our own standards, much less God’s. Ever since Adam and Eve, people who have done wrong have shied away from God, fearful of having their own “sorriness” confronted by God’s holiness.

The only thing that can reach us in such a state is a clear message that God’s love is greater than our failure – that God’s love is so deep, broad and total that it can forgive and defeat even the darkest and most evil act. The cross stands as the centerpiece of a Christian people’s life together, a startling and sobering reminder that God’s love is free but it is not cheap. God’s love is so complete that God in Christ was willing to suffer and die so that we could be forgiven and live.

We use the word “communion” to refer to the Lord’s Supper so much that we are in danger of forgetting it’s other meanings. It refers to the connection and community of God the Father and God the Son and God the Holy Spirit in the one Godhead and to the connection and communion of all of us as individual Christians who are yet one body of Christ in this congregation, and the connection and community of this congregation with other congregations and with the Trinity in the universal, worldwide, all times and all places thing we call the catholic church. We gather for the meal that celebrates and solidifies this Holy Communion to remember that we are a community united in Christ that is called to constant love and forgiveness of each other and the world. That is why the table is always open and inviting to all – calling everyone to the place where God’s love and forgiveness are made real and touchable in the body and blood of Christ.

Elaine Pagels is a New Testament scholar who has readily admitted over the years that she is not active in the church, that she does not believe what the church teaches. Yet, in her book “Beyond Belief,” she was honest enough to write a personal testimony about the value of the church. The day she discovered that her young son had a terminal illness she found herself in the back of a church, not remembering how she got there. After a while she decided to stay, thinking that she needed to be there, that it was good to be there. She writes: “… here was a place to weep without imposing tears upon a child, in a community … that had gathered to sing, to celebrate, to acknowledge common needs, and to deal with what we cannot control or imagine.”

That is who we are. That is who God has called us to be. We are a place and people who say to the world. “You are loved; you are forgiven; dinner’s ready – come eat.” “You belong here; you are a part of us.”

Amen and amen.