Lectionary for Aug 16, 2020

Eleventh Sunday after Pentecost

Isaiah 56:1, 6-8; Psalm 67;

Romans 11:1-2, 29-32; Matthew 15:21-28

Let’s not mince words: This week’s Gospel text is uncomfortable. And it’s all the more uncomfortable during a global refocusing on the evils of systemic racism. The holy response to Scripture passages that make us uncomfortable is exactly the same as the holy response to racism—dig in, get curious, and start exploring what’s going on and why.

For starters, we have to contextualize both who Jesus is and where Jesus is.

First, the Gospel of Matthew points out, purposefully, that Jesus has Canaanite and other foreign women as ancestors (Matthew 1:3, 5 and possibly 1:6—see 1 Chronicles 3:5, c.f., 2 Samuel 11:3 ). The foreign magi play an important role in Matthew as some of the first witnesses of Jesus’ messiah-ship (Matthew 2:1-12). And Jesus has already ministered to Greco-Canaanites from the Decapolis (Matthew 4:25), commended a Roman centurion’s faith above anyone in Israel (Matthew 8:10) and exorcised demons from Canaanites (Matthew 8:28-34). True, Jesus told his disciples they should only go to Israelite villages for their training exercises (Matthew 10:5-6). But his ultimate goal, we must remember, is training international—global!—disciples (Matthew 28:19). We need to read the story of the Canaanite woman canonically, in light of Jesus’ identity and ministry.

Second, and maybe even more importantly, we need to pay attention to where the Gospel writer tells us this conversation takes place. Jesus had just finished an argument with his Pharisee colleagues about whether one had to follow the extra-biblical tradition of washing hands before one eats. While it is a good idea to always wash hands, eating with unwashed hands doesn’t defile the food or the person who eats it (Matthew 15:20). Peter noted that Jesus’ response had been particularly offensive to the Pharisees (12). So Jesus left that place and went to the region of Tyre and Sidon, which wasn’t a short journey. Historically this area was home to the worship of baal, and the residents didn’t always get along well with Israelites—or vice versa. Jesus didn’t end up here accidentally—he intentionally left Galilee and traditional Israelite and Jewish lands to be among the people of Tyre and Sidon.

It matters that Jesus told his disciples that he was only sent to the house of Israel before the Canaanite woman even approached him to speak. Jesus wants them (and us) to learn something.

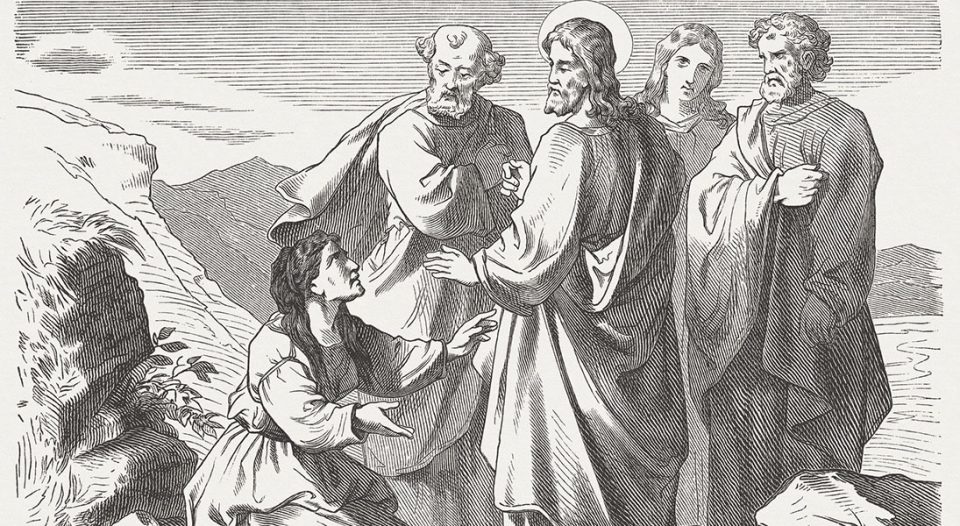

So we turn to the Gospel with the understanding that Jesus—who Matthew has told us is part-Canaanite and has conducted ministry, including healing from demons, among these people—has come to Canaanite territory. Unsurprisingly, Jesus was approached by a Canaanite woman who cried out to have a demon exorcized from her daughter. Yet he didn’t answer her with even a word. The disciples implored him to drive her away, but he refused to dismiss a woman so in need. Jesus replied to his disciples that he was only sent to the lost sheep of the house of Israel (24). We need to understand that Jesus was toying with the disciples here. Obviously, he had already ministered to non-Israelites. Even more so, if Jesus had only been sent to the house of Israel, what was he doing in Tyre and Sidon? This wasn’t the first time Jesus had temporally left Israelite/Jewish territory for Canaanite land.

Something else is going on here. I think it matters that Jesus told his disciples that he was only sent to the house of Israel before the Canaanite woman even approached him to speak (25). Jesus wants them (and us) to learn something.

The Canaanite woman then came and bowed to Jesus, asking for help. Jesus answered with another statement that seemed to indicate he wouldn’t help her: “It is not beautiful [καλὸν] to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.” Please don’t let anyone soften this passage by talking about cute little dogs. This was an unkind thing to say. And it is exactly the sort of thing that people said about Jesus opening up the kingdom of heaven to gentiles, particularly since some ways of understanding food laws in the early church made it more difficult for Christian Jews to participate fully.

The question is not one of sharing the children’s bread, but of taking it away and throwing it to others. Jesus anticipates criticism of exactly the sort of outreach that he had been doing and would continue to do. He says what he does for his disciples to hear, as they also see the woman at his feet, begging for him to help her daughter.

And this is the best part of the story, and one of my favorite sections of Scripture: the Canaanite woman has no time for being an object lesson on how the disciples should confront their racial-religious prejudices. She tartly responds to Jesus, who may not have even spoken the last sentence to her but to his disciples: “Yes Lord, but even the dogs feed on the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table.” This is so brilliant, so cutting and so funny. The woman reminds Jesus that he is in Sidon, where there are no Israelite children anxious to feed on this bread of life. Instead, she calls Jesus a crumb that has fallen off the table, with no one even noticing. She is content with the self-exiled messiah because he is all she needs for her daughter to be made well. Hearing her super-witty retort, Jesus calls it “great faith” and heals her daughter on the spot.

I don’t think Jesus was being racist. That is completely counter to the image of Jesus that the writer of Matthew is trying to present. We need to remember who and where Jesus was, and pay attention to whom he was speaking and for what purpose. Jesus was challenging his disciples to expand their vision of the kingdom of heaven. The Canaanite woman didn’t have time for an anti-racism lecture and challenged Jesus to provide for her then and there. Jesus was obviously delighted with her response and healed her daughter.

The moral of the story is that Jesus will work to undermine human separations in the minds of his followers at the same time that he will cross those barriers himself.