As the daughter of an ELCA pastor, Eleanor Jerbi has spent a lot of time in churches. And as a neurodivergent person—Jerbi has dyslexia, dyscalculia, dysgraphia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—she knows that church may not feel like a welcoming sanctuary to everyone.

“Especially in smaller church buildings, services can be very overwhelming just because of the way the sound system works,” she said. “And in big churches, you need to have it loud enough that people can hear it, but not so loud that musicians can’t play. It’s a balance, but for neurodivergent people, that nice balance to everyone else can still be too much.”

Neurodiversity is a term that describes cognitive differences between how people think, learn and behave. Most people fall within one of two categories: neurotypical, which means they process information in a way considered typical for their age, and neurodivergent, which means they process information in a manner atypical for their age.

Neurodivergence can refer to several conditions, such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia and dyspraxia, among others. But neurodivergence is not a diagnosis—it’s merely a blanket term indicating that a person’s brain works differently from what is considered typical.

What does that mean in terms of individual behavior and needs? There’s no one-size-fits-all answer—some people may be hypersensitive to stimuli such as light and sound while others crave sensory interaction with bright colors and textures.

With more awareness of neurodivergence and the specific needs of these individuals, ELCA communities are working to foster more inclusive spaces that make everyone feel comfortable and welcome.

“We’re trying to promote awareness about the importance of inclusion,” said Lisa Heffernan, coordinator for ELCA Disability Ministries. “We do a lot of teaching of ways to make the church more inclusive and accessible, and that each person has a place and purpose in the body of Christ.”

Listening and learning

For neurodivergent children and their families, attending worship services can sometimes be a challenge. Even the most neurotypical child can struggle with sitting in a pew for an extended period. Those who process stimuli differently may find services nearly impossible to endure without accommodations.

This became an issue for Kristin Thomas Sancken—who has attended Lutheran and Episcopalian congregations and writes regularly for the ELCA—and her child, Oakley, who was diagnosed with autism at age 8. The Episcopalian congregation Sanken attended at the time rented space from a school that, due to liability issues, prohibited unattended children in the hallways. Oakley (who uses they/them pronouns) felt overwhelmed by the sights and sounds of the service and spent much of their time in the hallway. Sancken feared that this new rule would make church impossible for their family.

When Sancken brought her concerns to the pastor, he made a concerted effort to get to know Oakley and make accommodations for how they experienced church.

“Our pastor sat with us and watched Oakley and got to know Oakley,” Sancken said. “He talked to Oakley and asked about their questions about faith. And even if he couldn’t answer the questions, he found resources that could.”

“Each person has a place and purpose in the body of Christ.”

Sancken said many people with autism aren’t motivated by emotion in the same way as neurotypical people, so conventional worship isn’t as compelling to them. Instead of trying to reach Oakley on an emotional level, their pastor related faith to something that made more sense to them: nature.

“Oakley struggled with the idea of faith and has found faith more through nature and spending time outdoors—that has been really meaningful to them,” Sancken said. “And that’s one way our pastor adjusted—he has started to talk more about nature. Our Lenten theme this year was ecosystems and how the delicacy of these ecosystems teaches about the balance of God and how everything is so carefully and wonderfully made.”

Sancken believes that getting to know and understand neurodivergent people can make the difference between their dreading church and their feeling God’s love there.

“As parents,” she said, “we’ve had to let go of this idea that [our primary faith formation focus is] to raise them strictly as an ELCA Lutheran and think more about the end goal. It has been much more about hoping some of these prayers, some of these ways the church has tried to work together with us, has an impact on Oakley, and that when they face trauma in life, some of this will help them.”

Permission to play

Micah Garnett, pastor of Trinity Lutheran in Canton, Ill., knows well the challenges of making church accessible to neurodivergent children. His daughter was diagnosed with mild autism and cerebral palsy, and his neurotypical son has Marfan syndrome, a condition that affects the body’s connective tissues and can cause physical difficulties.

Living in a small community, Garnett’s family often had to travel to larger cities for the therapies they needed. After accompanying his daughter on a field trip to a disability-friendly camp, he got an idea for how Trinity could reach not only his children but others with similar needs in their community.

“They had this sensory activity fence, and I watched my daughter as she played with it and saw how much she loved it,” Garnett said. “I thought, ‘What if we had something like that here in our community?’”

Garnett took the idea to the vision team at Trinity with a twofold mission in mind: to create a space for neurodivergent children in their area while also inviting community members to the church. Trinity already participated in the Rejoicing Spirits ministry for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, so Garnett saw the sensory fence as a natural extension of that work.

“I thought, ‘What if we had something like that here in our community?’”

Using a parking lot it already owned and a grant from Grace and Peace Lutheran in nearby Peoria, the church built a wooden fence along one side of the lot and affixed a variety of sensory activity stations to it—everything from a xylophone and wheels to fidget toys and puzzles.

“It started in a minimalist way, with a lot of sensory toys from my home that my daughter no longer uses,” Garnett said. “Then folks from the church started donating things—knobs, switches, buttons, even an old-fashioned crank-style eggbeater.”

The fence was a hit among children, both neurodivergent and neurotypical, and the church began to think of ways to expand on it. Trinity received another grant this year, from St. John Lutheran Church in Springfield, Ill., that will allow it to install a second fence around the first one to separate it from the parking lot. It also hopes to create a second sensory-activity area so they can separate the loud toys from the quiet ones.

Garnett said a sensory wall can be a fairly cost-effective way to reach people not only in the church but also in the greater community.

“The amazing part is, this is actually a really easy thing to do because most churches have extra property somewhere, or they may have a fence already,” he said. “The idea beyond the sensory fence itself was us looking at our property and thinking about ways for our facility to do ministry itself.”

Amplifying awareness

Many adults also identify as neurodivergent. With greater awareness of and testing for conditions such as autism and ADHD, more adults who had gone undiagnosed now better understand how their brains work. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 15.5 million adults had a current ADHD diagnosis in 2023, and half of those were diagnosed at age 18

or older.

That was the case for Anna Gordy, an ELCA coach, mission developer and spiritual director in New York City who was diagnosed with autism at age 45. She said there are a lot of adults like her who are high-functioning and, in some cases, living with undiagnosed autism.

“I’m not the person people imagine when they think about an autistic person,” she said. “And there are a lot of undiagnosed folks out there who tend to have special interests in religion or have many autistic tendencies. A lot of those folks deeply connect with me right away.”

Autism spectrum disorder can impair social communication or interaction, and people can range from nonverbal to above-average intellectual functioning. According to the CDC, typical signs of autism spectrum disorder include avoiding eye contact, delayed language and movement skills, repetitive behaviors, obsessive interests and unusual reactions to sensory stimuli.

“The amazing part is, this is actually a really easy thing to do.”

Gordy said awareness and acknowledgment are key to creating a more inclusive church environment for neurodivergent people. That means cultivating an open dialogue, in which congregants feel comfortable voicing concerns about things such as light and sound in a church, and addressing issues in a thoughtful, respectful way.

“We have to be better, especially in the church, at believing people when they tell us things about themselves, and to not be judgmental about it, because we don’t know what somebody else is living,” she said. “And if something is small to us, like a blinking light, but is a big deal to them, then it shouldn’t be a big deal to us to alter it.”

Gordy points to ReconcilingWorks congregations, and how they create inclusive environments for people of different races, LGBTQIA+ individuals and others, as a guide to welcoming neurodivergent parishioners.

“When my children were younger and their dad was in the Navy, we moved a lot, so I always looked for a Reconciling in Christ (RIC) congregation because I knew those folks had done the work to be tolerant and welcoming,” she said. “I know not every congregation is going to become RIC, but they should do this kind of training in relation to neurodiversity.”

Evolving through education

Jerbi, a member of Immanuel Lutheran in Seattle, agrees that education is an important step for congregations that want to create a more inclusive environment for neurodivergent people.

“If you just give people resources and say, ‘Go have fun,’ that’s not going to help anyone,” she said. “You need to explain why you’re giving them this specific set of resources: Why am I giving you noise-reducing headphones? Why am I giving you fidget toys or unscented markers? These are oddly specific things, and if you give them to a church without any education about why those things are important, they aren’t as helpful.”

Jerbi has made it her mission to help congregations get the tools they need to better relate to neurodivergent people like herself. For her Girl Scouts Gold Award service project, Jerbi focused on making congregations more accessible to neurodivergent people, specifically children and youth. She began by conducting research on neurodivergence and then educating herself on how best to share that information with neurotypical people.

That work led Jerbi to create a training program that includes a slideshow, resource list and booklet to help churches be more inclusive to neurodivergent people.

“Most of the time, if you educate congregations and give them the proper resources, they will do what they need to do,” she said. “Education helps break down the stigma around disability.”

“Education helps break down the stigma around disability.”

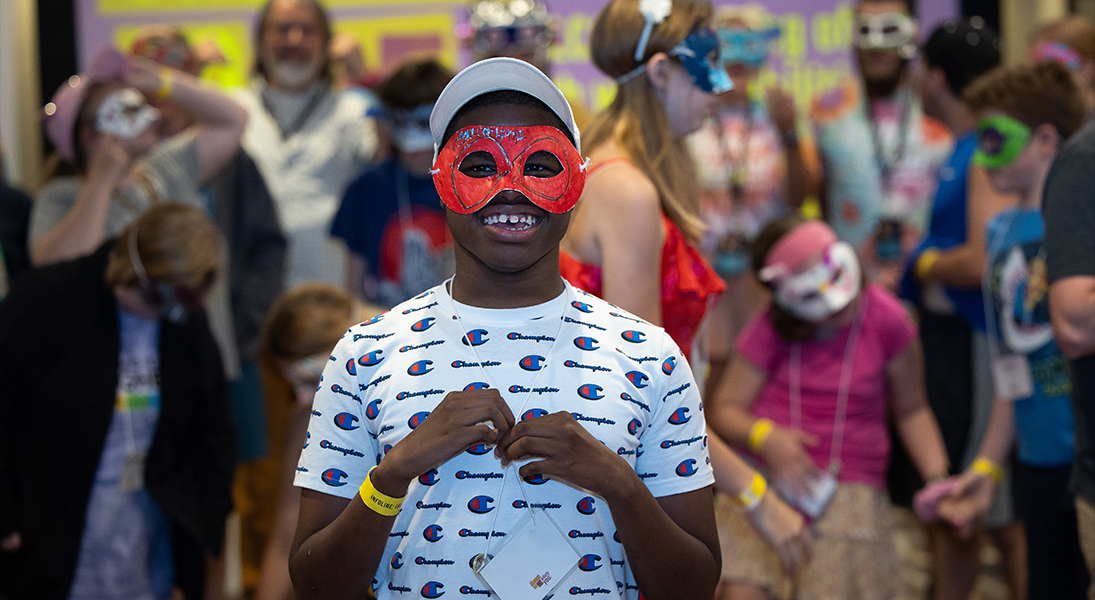

During the 2024 ELCA Youth Gathering, Jerbi attended the tAble, a smaller gathering of neurodivergent and differently abled young people. Both there and at the larger Youth Gathering, she handed out fidget toys with links to her resource and training tools. She said the response she received and the acceptance she felt at those events made her optimistic for the future of neurodivergent people in the ELCA.

“Bishop Elizabeth Eaton showed up at the tAble, which was very nice to see because she didn’t have to do that. But she did, because it was important to her,” Jerbi said. “It was really important for us to know that this bishop is here for you and will show up as a pastor for you.”

Major change takes time, but these small moments of understanding, acknowledgment and acceptance can go a long way in making the ELCA a place where neurodivergent people feel at home.

Heffernan said the ELCA has moved past simple awareness to “creating action and encouraging the great work that’s already happening in our congregations. We’re learning what best practices are and what inclusion looks like in reality. The phrase I like to use is ‘thinking of what holy creativity is possible’ when it comes to inclusion and encouraging congregations facing the same challenges to network and come together to find solutions.”