Series editor’s note: We continue in the yearlong study of Reformation and Martin Luther studies themes, grateful that this month two church historians share their perspectives on the continuing relevance and unifying force of the Lutheran Confessions. —Michael Cooper-White

Martin Luther’s protest against the medieval church resulted in memorable slogans: “Faith alone!” “Saint and Sinner!” “Law and Gospel!” But the Lutheran Reformation succeeded and reached us in our time not because we won the slogan contest but because of a remarkable set of “confessions”—statements of faith—that continue to unite Lutherans and show us how to adapt Lutheran principles to new times and places.

From the beginning, Lutheran reformers did more than criticize and tear down the old—they built a new framework for thinking about and living the Christian life. Luther and his allies challenged Christians to search and ponder Scripture with fresh eyes, and to worship and live far differently than preceding generations.

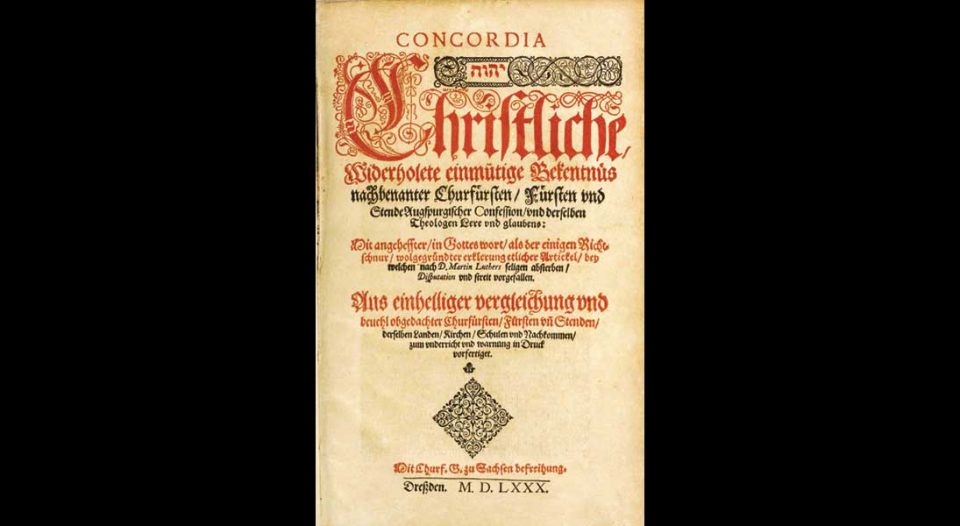

Intra-Lutheran controversies erupted especially after Luther’s death in 1546, and it fell to a new generation of reformers to chart the future course of the Lutheran Reformation in a manner faithful to its foundational biblical and theological insights. The labors of this generation led to the creation of the Book of Concord, first published in 1580. This extraordinary collection of key documents, including the Augsburg Confession and Luther’s catechisms, helped establish a Lutheran tradition of theological teaching.

Like the ancient Christian controversies over the nature of the Trinity and the Incarnation, the intra-Lutheran controversies of the latter 16th century were intense and divisive because they involved fundamental questions about Christian salvation and life. Lutheran reformers grounded salvation (aka justification) in God’s gift of faith in Christ, rather than in human efforts, and they argued that the life of faith was lived out most truly in the world, in the daily life of work and family, rather than in a monastery or on a pilgrimage. It took decades to even begin to work out what these radical claims entailed for Christians.

What is more, the compilers of the Book of Concord didn’t see their work as the end of the process. Instead, they sought to establish a lasting standard for evaluating doctrine and practice so future generations could continue to seek a deeper understanding and a more faithful application of the gospel.

Attributing the final authority to Scripture, they described the Augsburg Confession of 1530 as an authentic interpretation of Scripture necessary to meet the challenges of their era, just as the Nicene Creed applied Scripture to the challenges of its day. The Book of Concord also gives special authority to Luther’s two catechisms as constituting “a Bible of the laity,” thus affirming the Lutheran commitment to honor and transform daily life.

Lutheran churches have studied the 16th-century confessions and accepted them as their own in different ways. Some have accepted only the Small Catechism and the Augsburg Confession.American Lutherans couldn’t read an English translation until 1846. Translation efforts continue today for students around the globe, making Lutheran theological work possible in their languages.

Lutherans throughout the world find in the confessions a firmer path to unity and greater depth and persistence to diaconal service. Lutheran pastors pledge to preach and teach in accordance with the Scriptures, creeds and confessions, and our constitutions include the same commitment on the part of congregations.

Missionary fervor carried Lutheran teachings around the world, especially through the catechisms and hymns. As Lutheran churches came into their own in the former “mission fields,” they joined the war-shattered churches in Europe to form the Lutheran World Federation in 1947. The Lutheran Confessions provided the foundation for Lutherans worldwide to understand their purpose as a church among other churches, a faith among other faiths. Because they recognize their theological unity through the Augsburg Confession, Lutherans have made a path to unity around the world, and they have a language to pursue ecumenical and interfaith dialogue.

Just as the authors of the several documents in the Book of Concord foresaw, Lutherans have continued to have vigorous theological debates. But even as Lutherans debate the merits of revival conversions, the Augsburg Confession makes clear that we don’t save ourselves by our decisions—it is God who acts to save.

When Lutherans grapple over the ordination of women, a clear understanding of our salvation through God’s decision for us orients the discussion. Our human condition, whether male or female, does not influence God’s gift of salvation. God saves, and nothing in us makes us the instrument that God can use. “God’s work. Our hands.” applies to all of us. The core teachings of the confessions concerning justification and the dignity of daily life draw powerfully on the biblical message to free us for work in the world today.

The confessions unite us by enabling us, as a unified people, to do exactly what the first Lutheran reformers did: seek an ever deeper understanding of the gospel and our witness to it in a changing world.