Editor’s note: As Lutherans, grace is at the heart of our faith understanding. But what does it look like to actually live out grace? This is the final article in a series exploring what grace means and what it looks like to tangibly experience grace in action.

Each Saturday evening, the men of Living Stones Prison Congregation in Shelton, Wash., gather for worship inside the Washington Corrections Center. Like most ELCA congregations, Living Stones offers word, sacrament and a warm welcome to visitors—in this case, guests from congregations throughout the Southwestern Washington Synod who support the prisoners.

Melanie Wallschlaeger, the synod’s director for evangelical mission and its adviser to the Living Stones board, noted that visitors are often struck by the spirit-filled worship, much of which is led by “the guys,” including a 12-person worship band. “God is alive and well here,” she affirmed. As is grace.

Yet in today’s prison system, grace can be hard to find. While affirming the “fundamental principles of the U.S. criminal justice system such as due process of law and the presumption of legal innocence,” the 2013 ELCA social statement “The Church and Criminal Justice: Hearing the Cries” also recognizes that “an underlying punitive mindset, budgetary constraints and persistent inequalities based on race and class frequently challenge its basic principles and impose significant costs on all involved in the system, and on society as a whole.”

As Wallschlaeger said, “Aren’t [prisons] supposed to be places of reformation? But they don’t function that way.”

When grace manifests

Mike Davis, associate executive director of Prisoner and Family Ministry for Lutheran Social Services of Illinois (LSSI), agreed: “Prison is a traumatic experience. You’re told what to do 24/7, you’re under surveillance … the prison system is not a vacation. It’s a penalty, I get that. But you can’t put people in isolation and expect them to come out as a human being. You’re taking the humanity, the image of God we were created in, which sin has already eroded, [and] increasing that person’s dehumanization.”

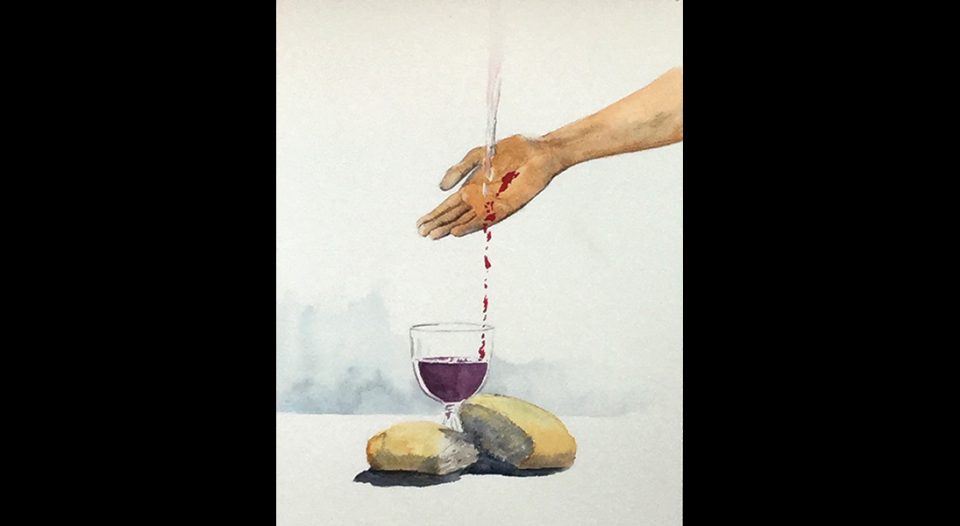

For this reason, LSSI’s ministry starts from a position of restorative justice: to help restore the image of God in those who have been incarcerated through services that touch the heart, the mind and the physical well-being of its clients, the organization says.

“Grace is manifested when we see the light switch on in body, heart and mind: ‘I am somebody, and this is my community.’ ”

Some LSSI services connect incarcerated parents with their children, including its Storybook Project that provides children with recordings of their incarcerated parents reading to them. Meanwhile, its Re-entry Services for Returning Citizens programs help people transitioning out of prison with literacy, transportation, employment and life skills, including a community garden project and specialized training in solar panel installation.

This material help is crucial, Davis emphasized, because poverty and a lack of options greatly increase the likelihood of recidivism. But grace also goes further. Davis coined the term “returning citizens” as an alternative to “inmates” or “prisoners” to help LSSI focus on the humanity of its clients and help them “begin to understand that they’re somebody and somebody cares about them,” he said. “Grace is manifested when we see the light switch on in body, heart and mind: ‘I am somebody, and this is my community.’ ”

Living Stones also provides that sense of identity and community for those whose incarceration is ongoing. “It is in every way a congregation—the men lift each other up in prayer and support one another,” Wallschlaeger said. That support extends beyond the prison as well: in addition to the many visitors to worship, Living Stones’ newsletter publishes poetry, artwork and reflections from the men and Chris Ode, Living Stones’ pastor, visits synod congregations to preach and bring greetings.

“The very face of Christ”

This partnership in grace has other examples in the synod. Empowering Life at the Washington Corrections Center for Women in Gig Harbor, Wash., began as a pastoral care ministry by a trained layperson, Sharon Peterson, and grew to include a Lutheran worship service led by local clergy and coordinated by St. Mark Lutheran Church by the Narrows in Tacoma.

Originally held only four to five times per year, Empowering Life Worshipping Community now leads biweekly services. Financial support from Lutheran congregations and organizations has allowed mission developer Joan Nelson to focus on “bringing in people to lead worship who reflect the population,” Wallschlaeger said, including young women and women of color.

As these ELCA members and others in prison ministry have learned, grace in prison flows in both directions. As Wallschlaeger put it: “It’s not that we bring grace to [incarcerated people], but that [they] are for us the very face of Christ.”