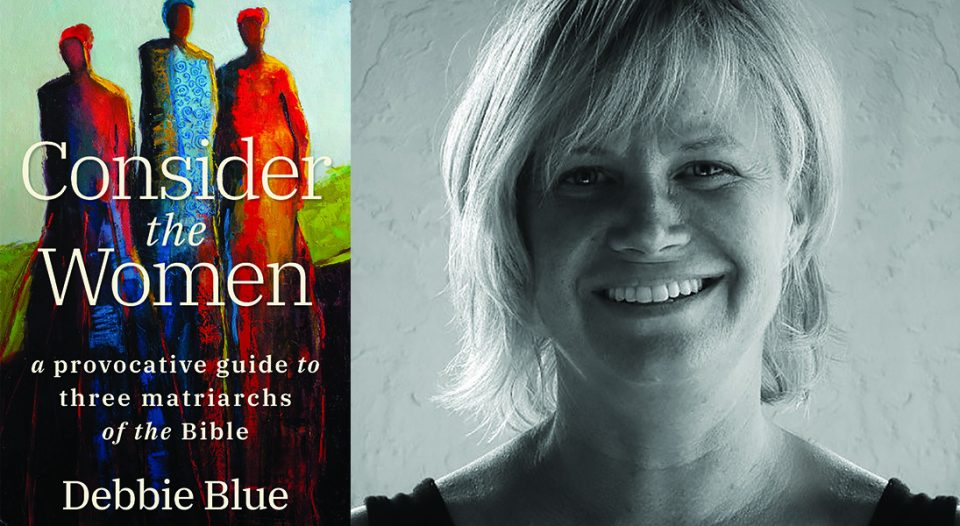

Debbie Blue’s new book Consider the Women: A Provocative Guide to Three Matriarchs of the Bible (Eerdmans) offers readers an expansive invitation to think more deeply about the lives of Hagar, Esther and Mary, exploring their stories both inside Scripture and elsewhere.

Living Lutheran spoke with Blue, an ELCA pastor at House of Mercy, St. Paul, Minn., about female narratives in the Bible and how feminine metaphors for God enrich her faith.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell us about Consider the Women?

Blue: At its most basic, it’s about women’s stories inside and outside the Scripture, and it’s about how focusing on women’s stories can change the way we see God, and can change the way we understand faith, even. For me, they do help us see a God who is boundary-breaking, a God who doesn’t draw lines as much as cross over the lines we draw. Obviously, our world is really divided now, and I think we need these stories that help us cross the divides instead of the stories that keep reinforcing them.

Of course, the Bible has been used in destructive ways, ways that have been really damaging to people who aren’t straight or who are not white, [and to] women. It’s built walls and got people believing in these walls at times. But that doesn’t have to be the way we read the story. The book is about saying, “Let’s start understanding those stories in different ways.” It’s about engaging old stories in new ways and about looking for ways to cross the divides. [These women’s] stories have really helped me to do that, and I wanted to introduce readers to that.

It’s also about bringing out the feminine images of God in the Bible, because they haven’t been given as much play as the masculine images of God. I really think it’s time to retire this mythos around stories of the lone, charismatic [male] leader. I don’t think that’s been working out so well.

What was your inspiration for writing the book?

I’ve been preaching [for] about 30 years now, but every time I’m preaching and there’s a story about a woman that comes up in the lectionary—which is, surprisingly, not that often—I’m so happy. I get a lot of energy in writing about those texts. The minister part of my job is to deal with the texts and traditions of Christianity, and it’s kind of hard, as a woman, not to notice that it’s all overwhelmingly male. So when the women and the feminine images of God show up, I feel like, “Let’s pay a lot of attention to them.” I’ve had a lot of energy around doing that and also bringing out the ways that patriarchy has influenced our tradition in damaging ways.

Hagar, Esther and Mary were all such interesting characters to me. I kept wanting to follow them beyond the confines of what a sermon allows, outside of the text and through history and culture, because they are really remarkable characters in the Bible, and then they go on to be these provocative characters outside of the pages of Scripture.

You invite readers to approach the Bible through engaging with questions, doubts, cultural context and our own contexts. Why is it important to you to interact with Scripture in this way?

My book does that, but Scripture itself does that. I think that’s the way Scripture invites us to read it: it invites us to engage with it as very complex, faltering humans with brains and emotions and bodies. It invites us into relationship with the material as whole creatures, and it’s so obviously not an instruction manual. There might be a few places you can use it that way, but for the most part, it’s stories with all sorts of layers, and it’s poetry.

That’s how stories and poetry work—they invite questions and there’s room for doubts. It requires us to think and to ask questions and even to feel. To me, that’s a gift, because we need it so much more deeply [when we approach the Bible in this way] and it engages us as fully human beings.

“Focusing on women’s stories can change the way we see God.”

Are there elements you think will particularly connect with ELCA members?

I think Lutherans will connect with the foundational premise of the book, which is that our ways of interpreting texts and traditions are always in need of reformation or reforming. That’s very Lutheran.

When I first delivered this book to my editor, I wanted to call it “A Rambunctious Monotheism” because I’m not sure “mono” gets what we want. Maybe God’s more rambunctious than monolithic. You can tell from the proliferation of metaphors in the Bible that God is more like many things than one thing. God is a lily, a rose, dew, wind, fire. There are so many metaphors for God. So is God monolithic or is God more like many things? If people are really fixed on the idea that our way of seeing God is the right way and that we are the ones that finally pinned God down, then it could be challenging.

What are your hopes for readers?

I hope they’re inspired to look deeper at the stories of women in the Bible, to value those stories immensely, to not pass over them, to take a deeper look, and also to look for the things in their own lives that have broken down boundaries for them. Then to tell those stories and to realize how important that kind of story is now, these stories that cross the divisions instead of reinforcing them.

I want them to not feel stuck in the patriarchy that we find in our traditions and texts, because there’s so much else there [that] we may need to dig around to find them sometimes. I hope they leave with the recognition that it’s important that we dig if we have to—it’s actually crucial.

Your book only begins to scratch the surface of women in the Bible who are a lot more complex than we might remember from Sunday school. Are there stories of other biblical women you’re particularly drawn to?

Miriam is so interesting, but becomes so much more interesting when you look at her stories in the Midrash. The Rabbinic writings suggest that she was a leader on par with Moses.

I’ve read amazing stuff about Potiphar’s wife. She’s not really thought well of in the Judeo-Christian tradition, but there’s a lot about her in Islam. Her longing for Joseph in the Islamic tradition comes to represent the soul’s longing for God.

Zelophehad’s daughters [appear] at the end of Numbers and they challenge Moses to give them their piece of the land—it was actually what their father was promised—and Moses does. He inquires of God and God says, “Yes, give it to them.” They are very cool figures that I hardly have heard anyone preach on.