When Grace Lutheran in Clarion, Pa., undertook a major building project—adding two floors of offices and classrooms to the back of its church building—signs that the small congregation was struggling started to become visible in the second year of the project.

When Grace Lutheran in Clarion, Pa., undertook a major building project—adding two floors of offices and classrooms to the back of its church building—signs that the small congregation was struggling started to become visible in the second year of the project.

“It was the decision-making,” said Harold “Jake” Jacobson, a pastor of the congregation. “Because the council was involved in the fundraising and the overseeing of the project, all of the decisions they had to make really wore them down. It’s having to think through things they’ve never had to think about.”

Once the construction was completed, the congregation intentionally took a break from any major changes or projects. “I didn’t throw anything at them for a year,” he said. “I’m not sure they knew that, but they didn’t complain either.”

Grace’s experience was an apt lesson about recognizing and healing burnout among church volunteers. It’s a lesson that resonates today as congregations return to in-person worship and other activities three years after the COVID-19 pandemic shut down churches and altered congregational life.

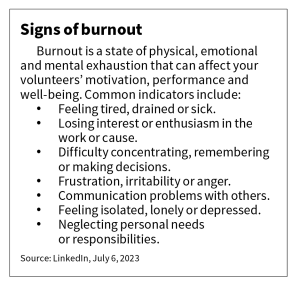

While burnout of rostered ministers post-pandemic has been widely acknowledged, burnout of active members of congregations is also being felt. As congregations ramp up programs after a summer respite, there are ways to recognize the weariness and lift up the ministry of the people.

1. People are tired. Say that.

At Christ Lutheran Church in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, fewer people attend worship than in the past, but tasks still need to be done. “When people stream from their living room, there are many people participating in order for the service to happen, so the people who are doing it are also the people who are doing this and that,” said Amsalu Geleta, a pastor of Christ Lutheran. “Yes, people can stay home and still participate, but if there are 20 ushers, half of them are streaming. You only have the same ushers who are doing it over and over. Acolytes, people who set up communion, clean up communion, readers. I’m worried they will be burned out.”

Phil Gustafson, a retired pastor who works as a life coach and is the coach coordinator for the Grand Canyon Synod, said rostered ministers need to give people permission to talk about what they’re experiencing. “Sometimes pastors get busy putting out fires, and we don’t listen to what a person is saying,” he said. “We miss the backstory behind what a person is doing and it further alienates.”

Since congregations began resuming in-person ministry, Gustafson said, fewer people have been willing to participate. Some people fear being exposed to COVID or made life changes during the pandemic. “For some, it was reluctance to try to do things as they used to be,” he said. “Whereas before, they were going to choir every week and there were connections. Then there was the period when they didn’t do that, and they decided they don’t want to expend energy they don’t have. They don’t want to be in choir again or on a committee again.”

As a coach, Gustafson tries to ask questions to help people uncover the reasons behind their reluctance. “I ask, ‘When did you last experience joy with this?’ ‘Is it life-giving? If not, why should you be doing it?’ Respect where people are, and probe deeper.”

Congregation members also might be experiencing fatigue because they’re so busy doing the work of the church that they aren’t experiencing the church. “There’s a diminished number of people doing more and more stuff,” Gustafson said. “You don’t have time to just be at church and worship and be replenished. It’s OK to say that.”

2. Recognize that the pandemic brought layers of grief.

Among the losses experienced by people “is that we are never going to be the church we were pre-pandemic,” said Chon Pugh, pastor of Mem1 (Memorial Lutheran and First Presbyterian) Church in Texas City, Texas. “It’s a loss. You’re grieving that. We are a grieving church right now.”

Mem1 is interdenominational, uniting two churches into a single congregation that worships and works together. The churches merged just before the pandemic, and Pugh was called as the first pastor in September 2020.

While parishioners are glad to be together, Pugh said that the identity loss of the individual churches is real, coupled with having fewer active members post-pandemic. Pugh said naming the grief is important.

“Have a campfire, write down the losses, put it in the campfire.”

“We’re never going to be what we were in the ’80s or the ’90s. That’s just not going to happen,” she said. “We have these huge churches that are absolutely gorgeous with a lot of history in them of generations and generations and generations, and pastors are working to get money just to keep the building going.

“[At Mem1] everyone had been working extra hard to make sure everything worked. I told the council, ‘I think everyone is exhausted. Let’s take the summer off.’ There have been no council meetings, no worship committee meetings. People are having meeting fatigue. I suggested that the choir stop, too, but they said, ‘Oh no, we get too much enjoyment out of it.’”

Pugh said she’s had three council members ask to step down because of the weariness of loss and change. “You just get tired,” she said. “Even if it’s just one night a week, it’s that one night a week.”

Pugh suggests finding ways to acknowledge the loss. “Have a campfire, write down the losses, put it in the campfire,” she said. “It might be COVID, it might be we’re not going to be pre-pandemic size, pre-1950s size, but it’s real. Name it.”

3. Do we have to do this?

Many churches returned to in-person worship and activities after 2020 shutdowns, but not everyone was willing to jump back into volunteering. Gustafson said churches can decide “to take a hard look at [ministries]. Even if we’ve done this for all of these years, if it’s not doing us any good, we can shut down ministries.”

He asks two questions: Is what we’re doing honoring God? Is what we’re doing building up the body of Christ? “If it’s not doing those two things,” he added, “why are we doing it?”

Pugh said every activity or ministry in a congregation needs at least one person who is passionate about it. A long-standing ministry might lose steam because of transitions in volunteers, and sometimes people need to be given permission to end an activity or ministry when that happens. “Just because it’s always been done doesn’t mean it has to continue if there aren’t people passionate about it,” she said. “I have no problem ending ministries because of that.”

Sometimes, Gustafson said, a new perspective can help breathe life into a tired ministry. He encountered this as an interim pastor when a neighboring congregation considered discontinuing a long-standing sandwich ministry because of a shortage of workers.

“But there were people who were getting meals, and those who were doing the work were focusing on the inconvenience,” he said. “The pastor was able to connect them to some of the recipients. That turned those members around. Instead of saying, ‘It’s pointless what I’m doing,’ it turned into, ‘I’m helping other people.’ The members doing the ministry doubled in size because they knew they had a purpose.”

Gustafson said one of the gifts of the pandemic might be that congregations have the opportunity to look at their menus of activities and question whether they should all continue.

“Do we need all these activities?” he asked. “If we’re just doing the same old, we want the church of the 1950s and try to program that way. But we’ve become more like a church of the first century, and re-created ourselves or re-presented ourselves with the advent of many churches using online technologies, learning how to live as a hybrid of virtual and in person.”

In this hybrid world, Gustafson said that it’s also OK to question continuing certain ministries, especially when there’s a longing to go back to what used to be. “It’s a curse when I’m doing something at church because my mother did it and my father did it and my cousin twice removed did it,” he said. “Is [the ministry] still something that works? How can we make this for the 21st century and less the 1950s?”

There are ways to recognize the weariness and lift up the ministry of the people.

4. Help people weather criticism.

It’s an age-old problem: active church members feeling hurt because other parishioners are critical when a project has glitches or something doesn’t go according to plan.

Technology has brought new opportunities for people to complain in a culture where critics seem more vocal than ever.

At Christ Lutheran in Baltimore “the people who are online, sometimes they are not grateful to people who are in person doing the things that make it easy for them to be at home watching,” Geleta said.

The church has a team of six to eight people who have managed the technology to stream services since the pandemic began in early 2020.

“If a microphone didn’t work or things happened beyond their control, people complained, people online complained, and that was harmful,” Geleta said. “Those are the new challenges. When things don’t go right, the mic doesn’t work, these are things that are silly, not theologically important, not a foundational change, but silly things. In spite of and regardless of the criticism, they’re frantic to make it right, but the one thing they should not hear is to be criticized for trying to run it smoothly.”

Geleta said it’s important for rostered ministers to be aware when that sort of public criticism is taking place and help provide tools and support for people to weather those storms.

5. Shower workers with thanks.

The list of active church members might be long or short. Thank them. Thank them again.

Gustafson remembers serving in one congregation where he was concerned that the person who mowed the lawn did it too often. It’s important, he added, to take even an activity that might seem mundane—lawn care at the church—and celebrate and express appreciation for that. Point out that mowing the lawn seeds the ground so that grass will continue to grow. “It’s part of that great circle,” he said. “Next year you’ll appreciate the work you’ve done to donate to the beauty. Yoke what they’re doing with something life-giving.”

Geleta said he tries to take every opportunity to lift up workers and thank them. “We make it a celebratory way of thanking them,” he said. “Make a day, or a time, for ritual installation of leaders, of Sunday school teachers.”

He also uses a weekly email to the congregation to praise those who are doing the work of ministry. “Every opportunity I get to lift up, I thank them,” he said. “I lift up things that people did or are doing, and then choose the gratitude part. That is the choice that I intentionally make. I find things that I think need to be thanked. I think it is catching up with people, and people are seeing that and then they do that too.”

He suggests being intentional about “speaking to the half-full part of it rather than the half-empty part of it.”

6. Simon sees. Simon says. Simon does.

Simon says might be an old children’s game, but seeing and following do actually work.

Gustafson said one way to help church members who are feeling burned out is for rostered ministers to model healthy ways they have found to handle the burdens of ministry in a post-pandemic world. “Focus on your own spirituality,” he said. “You can be so busy doing things that you’re not being spiritual. You pray, but you don’t engage in prayer for yourself. Or meditate. Or find a way to center.”

Since his retirement, Gustafson has served as an interim pastor in two congregations in transition. “When I model calmness and centeredness—if I pause and say I need to pray about this—by modeling, it gives people permission to do that, and sets an example.

“It’s ‘Physician, heal thyself.’ If you’re modeling anxiety, it will instill that in others. If you’re modeling calmness, it will instill that in others. If you want people to be spiritual, model your own spirituality, not just your head but your heart and your guts. Then they think, ‘If my pastor is doing this, then I can do it.’”

Jacobson, who serves a congregation and is director for evangelical mission in the Northwestern Pennsylvania Synod, said rostered ministers can model “the whole sense of letting go. There comes a time when we need to let go. And then we can pick up again.”

He said pastors tend to overwork and burn out because they think they have to do it all. “Letting go of that mentality has been exceptionally hard for pastors, given the professional model, because they feel called to do the work. We get sucked in,” he said. “But you can’t help anyone else unless you put the oxygen mask on yourself.”

7. Lift up and nurture future leaders.

Christ Lutheran has an expansive ministry that includes apartments for moderate-income older adults, a foundation, a nursery school, an outreach center and a parking garage. Each one is separately incorporated and each has a board that needs members. There are active members now, but Geleta said he is concerned about the future.

“Where we are not doing well, I think, is raising the people who will be stepping in,” he said. “That is a problem, will be a problem at some point.”

He said raising up new leaders might have occurred more naturally in the past, but now that needs to be a more intentional focus.

Any communication with members of the congregation is important. A quick text lets someone know that you’re thinking about them.

8. Communicate, communicate, communicate.

When people know they are valued, Gustafson said, they will give their best, adding that “the power of thank-you is an answer to burnout.”

Any communication with members of the congregation is important. A quick text lets someone know that you’re thinking about them. An email or a phone call can link rostered ministers to people. “Or you can go old-school and send a card,” Gustafson said.

Pugh writes birthday and anniversary cards to people. “It takes time, but that has helped through the pandemic,” she said. “And it’s not for everybody, I know that. If it’s not your thing, just find what your thing is.

She also tries to send texts to some homebound members every week to make them feel as if they are getting more individual time with the pastor. “But it’s short and sweet, and they can read it at 3 in the morning if they want to,” she said.

“I really think the key to it is we are here to serve God,” Pugh said. “At the Rostered Ministers Gathering someone said, ‘Every night God stays up creating a new day, and we wake up to that new day, and it’s up to us how we’ll use it. Remember that this is the day that the Lord has made.’”

Resources

- The Essential Guide to Burnout: Overcoming Excess Stress by Andrew and Elizabeth Procter (Broadleaf Books, 2019).

- How to Mobilize Church Volunteers by Marlene Wilson (Fortress Press, 1983)