In the last days it will be, God declares, that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh … (Acts 2:17).

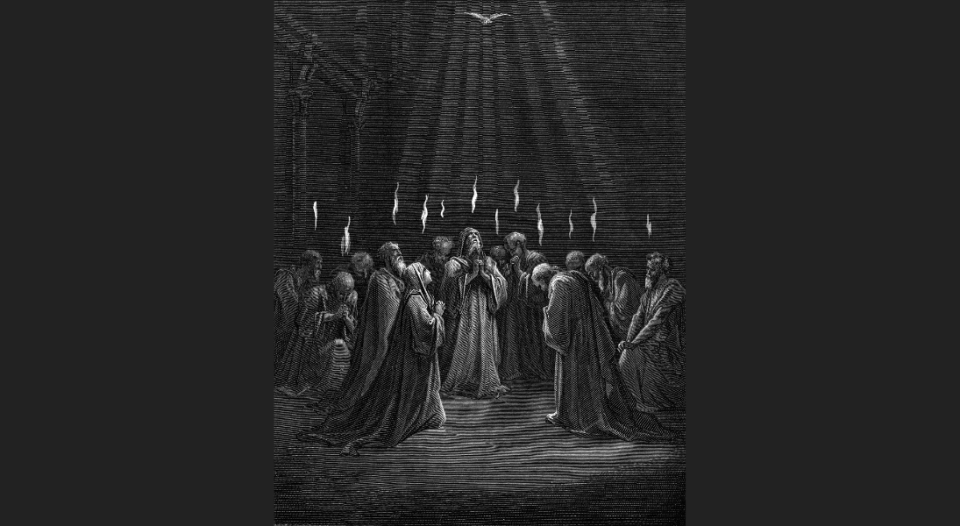

I forget sometimes how afraid the first disciples were. Not just in the shadow of the cross but even seven weeks later, on that first Pentecost morning. The tomb is empty. Christ is risen. And still—they are afraid.

Afraid of an empire always on the edge of crushing rebellion. Afraid of religious leaders more invested in control than in compassion. Afraid for their future, wondering, “What will happen to us?”

And then the fire comes—flames filling the house. Before they were awestruck at the power of the Spirit, surely they were afraid.

I think many of us today are also a little afraid of Pentecost. We smile politely at the story each year, but deep down we worry. After centuries of Christian colonialism and cultural dominance, it can feel disingenuous to speak with boldness. We’ve grown hesitant. Cautious. We wonder if Pentecost is now more of a memory than a mission.

But here’s the truth: it doesn’t have to be.

We could speak again. We could proclaim the love and liberation of God into broken hearts and broken systems. We have tools the early church never dreamed of—phones, platforms, global networks that cross every conceivable barrier. But still, we hesitate.

It’s not because we lack resources. We have them—right in our pockets, in our inboxes, at our fingertips. We have access to entire worlds of language, story, experience. With the smallest amount of humility and intention, we could learn to speak across divides of generation, race, gender, class, ability and culture. We could learn to listen—and then speak with clarity and compassion about the marvelous work of God.

And yet, in large part, we do not.

For decades now, we in the ELCA—and in many mainline Protestant spaces—have been asking, “What will happen to us?” Will our congregations survive the shifting culture? Will young people come back? Will there be enough pastors, enough members, enough resources?

And all the while, a revolution in communication unfolded around us. And we mostly watched it happen from a distance.

We kept preaching and teaching in the language that comforted us, hoping the world might come to us on our terms. We longed for “in-person ministry” even as the digital world shaped younger generations—often more powerfully than we did. Many of our young people were discipled not by churches but by algorithms offering certainty and superiority dressed up as belonging: white supremacy, misogyny and authoritarianism whispering false promises of purpose.

And still we wait for them to speak our language.

But Pentecost tells a different story.

It tells us that if we are to proclaim the good news, we must speak their language.

That might mean literal languages—Spanish, Somali, Lakota. It might mean moving from bulletins to Instagram, from theological jargon to storytelling, from newsletters to voice notes. But whatever the form, the call is the same: step out of your comfort zone. Learn. Risk. Speak.

And yes, it’s frightening.

When we choose to speak the language of others, we have to let go of the safety of our own fluency. When we stop relying on “how we’ve always done it,” we risk discovering that it hasn’t been working for quite some time. When we move from catechism to conversation, from certainty to compassion, we risk being changed. When our doctrine meets someone else’s lived experience, the gospel may take on a new shape—one that still frees but does so in ways we hadn’t expected.

That vulnerability is holy. And it is the heart of Pentecost. Because here’s the promise: it is not all up to us.

When Peter stands before the crowd and explains what has happened, he doesn’t point to his own eloquence or expertise. He doesn’t say, “Look what we’ve learned” or “Look how brave we’ve become.” He says, “This is what was spoken through the prophet Joel: ‘In the last days it will be, God declares, that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh ….’”

This is God’s work. But we are called to participate. And when we do—when we dare to step into that calling—we just might witness the miracle again.

When we choose to speak the language of others, we have to let go of the safety of our own fluency.

We might see a church that speaks to every generation, not just the ones who built the pews.

We might hear the gospel proclaimed in voices that had long been silenced.

We might find ourselves transformed too—our understanding of God’s love deepened by listening to the ones we used to overlook.

“Are not all these who are speaking Lutherans? But how is it that we hear, each of us, in our own native language? Gen X and Gen Z, artists and scientists, stay-at-home dads and single moms, male and female and nonbinary, third-shift workers and undocumented immigrants, neurotypical and neurodiverse—in our own languages we hear them speaking about God’s deeds of power.”

So let us not be afraid.

Let us be open—to learning, to listening, to speaking differently for the sake of the gospel.

Because the Spirit is still being poured out. And the world is still listening.