“Thoughts and prayers.” We’ve all heard this phrase in the wake of recent national tragedies, particularly in regard to gun violence, in what has become the routine offering of condolences from public figures to victims and their families.

Critics suggest that citing only “thoughts and prayers,” without committing to tangible plans, is an insufficient way to address complex issues. If our prayers aren’t accompanied by action, goes the argument, offering them becomes merely a platitude.

That raises the question of how we are to offer our prayers—and why we even do so to begin with.

For Lutherans, prayer isn’t only an individual discipline we practice daily on our own, but a communal one we return to weekly in Sunday assembly; not a passive gesture, but an embodied one, engaged as a way of participating in the work God is already doing.

Importance of prayer

Lutherans understand the importance of prayer. Martin Luther’s written prayers suggest someone in continual conversation with God. We know well passages like “pray without ceasing,” which Paul writes in 1 Thessalonians 5:17. Prayer is a meaningful ongoing practice for us—and, data may suggest, for most Americans.

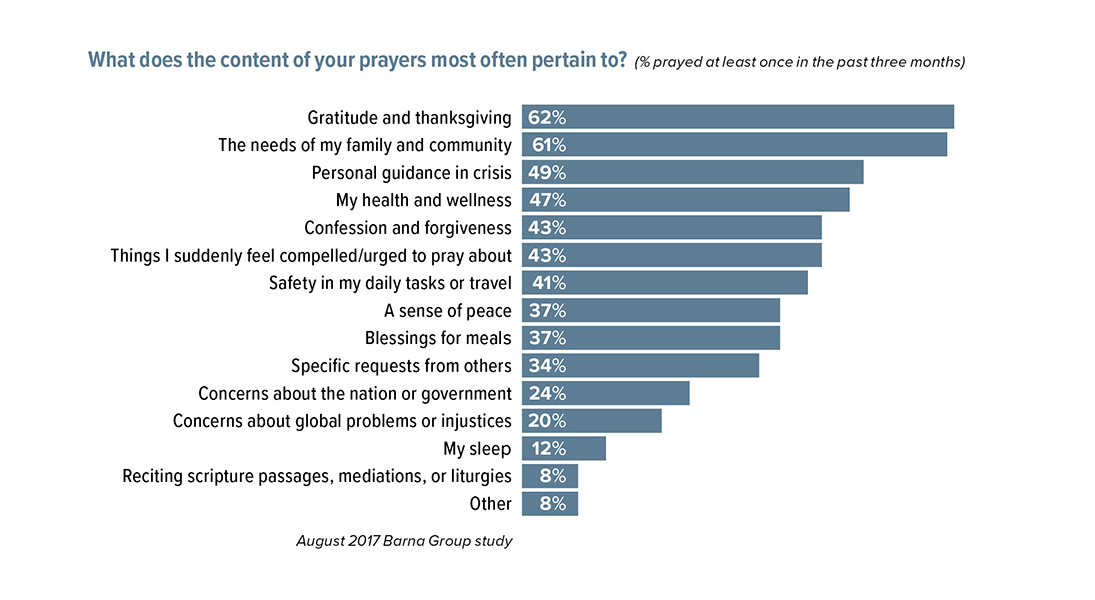

According to a Barna Group study from August 2017, 79 percent of American adults say they have prayed at least once in the last three months. The content of their prayers is wide-ranging.

Aside from “gratitude and thanksgiving” at the top and “reciting scripture passages, meditation or liturgies” and “other” at the bottom, all other prayer topics are asking for help in some way.

This makes sense, to a certain extent. In prayer, we admit that we are in need and we ask God to help us with those needs. If we, however, become too focused on our own needs, Luther said—or if we begin to feel that God isn’t “granting” our desires—we miss the point of prayer.

Making prayer solely about what’s happening to us, and subsequently feeling our prayers are not immediately “answered,” allows us to fall into the trap of asking, “Who knows whether God will hear and regard my prayer?” We then run the risk of entering “into the habit of never praying,” Luther wrote in the Large Catechism (Book of Concord, page 441).

Rather than getting stuck in the notion that whether or not we pray makes no difference in our lives, Luther emphasized God’s command for us to pray and God’s promise that our prayers are heard.

“The first thing to know is this: It is our duty to pray because of God’s command,” Luther wrote. “For we heard in the Second Commandment, ‘You are not to take God’s name in vain.’ Thereby we are required to praise the holy name and to pray or call upon it in every need. For calling upon it is nothing else than praying.”

Praying like this, within the context of a continuous relationship between us and God, requires a shift in thinking of prayer as a way to mold God to our needs to, instead, a practice focused on being shaped by God. A Lutheran approach to prayer is less about what we understand God to be revealing to us, and more about shaping our expectations for encountering and reflecting God’s grace in our lives and in the world.

Prayer changes us

If Lutheran prayer is a way of both sharing our concerns with God and enacting our baptismal calling to respond to the needs of the world, it is also a means of changing our mindset from one focused on ourselves to one centered on God and each other.

“Prayer is reorientation away from the preoccupations of this life toward the large, beautiful and trustworthy realm of the Eternal One,” said ELCA liturgical and homiletical scholar Melinda Quivik, who serves as president of the North American Academy of Liturgy and general editor of the journal Liturgy. “Prayer is a form of metanoia (a change in one’s way of life), of turning to God, recognizing that daily life is ennobled and made gracious when we place ourselves in God’s hands.”

Our praying does not change God. Instead, it is a way for God to change us.

Our praying does not change God. Instead, it is a way for God to change us. Luther said as much in his explanation of the Lord’s Prayer from his Small Catechism (Evangelical Lutheran Worship, page 1163). If, as Luther said, God is going to do what God is going to do, even without prayer, then the only one being changed when we pray is us—and that’s a very good thing.

The ELCA resource “EveryWhere and EveryWay: Calling One Another to Prayer” notes: “We don’t just seek God; God seeks us. Even the inclination to pray is a gift from God. When the disciples met after Jesus’ death and resurrection, Jesus moved through closed doors to reach them. This image also exemplifies the way Christ can move into our hearts—open or closed—and abide in us. … God uses prayer to change us and change the world.”

Prayer isn’t about us getting God to see things from our perspective. It’s about God getting us to see things from God’s perspective, and about moving us from a place of self-focus to one of outward focus and community.

Focus on God

God hears all our prayers, even when we can’t find the words to say them. Paul reminds us of this in Romans 8:26: “Likewise the Spirit helps us in our weakness; for we do not know how to pray as we ought, but that very Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words.” But, as Scripture tells us, the spirit with which we offer prayers matters.

Immediately before Jesus teaches his disciples the Lord’s Prayer, he says: “But whenever you pray, go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you. When you are praying, do not heap up empty phrases as the Gentiles do; for they think that they will be heard because of their many words. Do not be like them, for your Father knows what you need before you ask him” (Matthew 6:6-8).

When we pray, we should do so with a focus on God and a desire to strengthen one’s relationship with God, Jesus says. The “reward” we receive from God in prayer is the change God works within us.

If we share our needs through prayer in the context of our relationship with God, we do so “in order that you may kindle your heart to stronger and greater desires and open and spread your apron wide to receive many things,” Luther wrote (Book of Concord, page 443). Our hearts—and, subsequently, our actions—are changed when we pray.

Prayer isn’t about us getting God to see things from our perspective. It’s about God getting us to see things from God’s perspective.

We find evidence for this throughout Scripture. Consider the prayers in the book of Psalms (which Dietrich Bonhoeffer called “the prayer book of the Bible”). “Fundamentally, worship in Israel was about the praise of God,” wrote Fred Gaiser, professor of Old Testament at Luther Seminary, St. Paul, Minn., in the school’s Enter the Bible resource on Psalms. “Just as particular lament psalms often move finally to praise, so also does the entire Psalter.”

Jennifer Baker-Trinity, an ELCA deacon, agrees: “The psalms embrace the spectrum of human emotion, from deep lament to ecstatic praise. As a basis for prayer, they help us find the words we need when we are not sure what to say.”

“The psalms form the basis of our communal song together, which has been, for me, a primary way to pray in community,” said Baker-Trinity, who also serves as program director for resource development (a shared position between the ELCA and Augsburg Fortress). “Praise and prayer intermingle. Yet expressing our need before God in song is one way we pray together as community.”

Embodiment of prayer

In the ELCA, our worship is formed by Evangelical Lutheran Worship (ELW), including prayers for individual and communal use. Gail Ramshaw, a scholar of liturgical language, suggested that a Lutheran approach to prayer is best understood by knowing the ELW well.

“To discover what Lutheran prayer is, read and sing through the entire Evangelical Lutheran Worship book—every prayer, all the psalms, each hymn,” said Ramshaw, who served on the Revised Common Lectionary design committee and on the Church’s Year task force for the ELCA’s Renewing Worship project.

Ramshaw holds up the ELW’s tradition and role in communal worship as being especially vital to how ELCA Lutherans are to pray. “And even if you are praying and singing your way through the ELW all by yourself, remember that your voice and heart are joined with those of ancient Israelites chanting the psalms, first-century believers singing Lucan canticles, medieval nuns and monks keeping the hours, African Americans singing spirituals, with Asian carolers, pilgrims at Taizé, hymn writers from Ambrose to Luther to Susan Palo Cherwien, and countless Lutheran congregations worshiping every Sunday of the year across the land.”

Prayer allows God to change us into the people God wants us to be: those who praise and trust God, regardless of what happens in life, in our daily practice and when we come together in worship, bound together by our church.

Baker-Trinity understands Lutheran prayer to be “embodied,” she said, adding, “It can be easy to think of prayer as just words, as something ‘in the head.’ For Luther, prayer involved the whole self. When we sing, stand, kneel, fold our hands or stretch out our arms, we embrace the God who became flesh in Jesus and in us.”

Lutherans pray not because God is there to grant our wishes or do what we want—or as a way to offer platitudes in times of tragedy. We pray because we want to see what God is doing in the world. We pray because we want to join with God and with others in living out God’s love.

We pray because we want to be involved in how God works in people’s lives. We pray because we want God to be the center of our lives instead of ourselves. And these changes take place in us throughout our lives, in seasons of joy and struggle—“without ceasing.”

Resources

Available from Augsburg Fortress:

- Bread for the Day 2019: Daily Bible Readings and Prayers.

- Luther’s Prayers by Herbert Brokering (2004).

- The Disciples’ Prayer: The Prayer Jesus Taught in Its Historical Setting by Jeffrey B. Gibson (2015).

- To Pray and to Love: Conversations on Prayer with the Early Church by Roberta C. Bondi (1991).

- Prayer: A Primer by Henry F. French (2009).

- Martin Luther’s Catechisms: Forming the Faith by Timothy J. Wengert (2009).

- Praying for the Whole World: A Handbook for Intercessors by Gail Ramshaw (2016).

- Lutheran Questions, Lutheran Answers: Exploring Christian Faith by Martin Marty (2007).