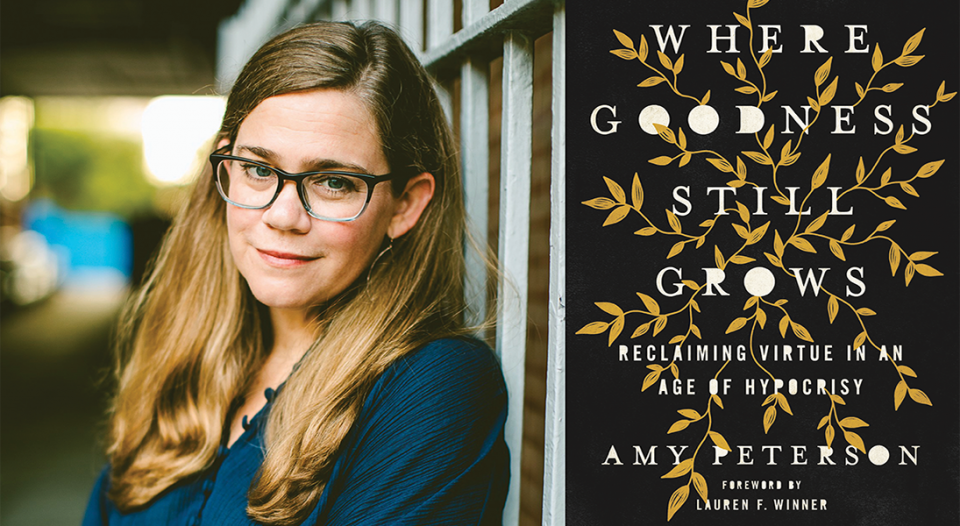

Amy Peterson’s spiritual journey began in the evangelical church of her youth, took her to Asia to do mission work, and currently has her pursuing a degree at Duke Divinity School, Durham, N.C., as a postulant in the Episcopal Church. Part memoir, part research, her new book, Where Goodness Still Grows: Reclaiming Virtue in an Age of Hypocrisy (Thomas Nelson), offers hope and an invitation to greater faithfulness, as well as an encouragement to engage deeply with loved ones with whom we may disagree.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell us about your book?

Peterson: Where Goodness Still Grows is the result of my wrestling with virtues from my childhood, trying to understand what embodied goodness ought to look like for me in this political moment. I devote a chapter to each of eight virtues. I interrogate each virtue, finding ways in which my [childhood] understanding of it was flat or one-dimensional—or finding ways in which my spiritual communities had used that virtue more as a weapon to keep people in their place than as a tool to cultivate goodness. Then I seek to expand and reimagine the virtue, listening especially to voices I rarely heard in my childhood churches.

What got you interested in exploring virtues more deeply?

I grew up with a copy of Bill Bennett’s The Book of Virtues (Simon & Schuster, 1996) on my coffee table, and with an understanding that Christian virtue was only to be found in one political party. … As the 2016 election drew near … I saw a major disconnect between the so-called “values voters” and the values I’d been taught by them. … So I set out to reexamine the virtues.

What were some of the biggest surprises for you as you researched definitions of virtue? What do you think will be most surprising for your readers?

One of the most fascinating findings for me was the connection between the way we understand authenticity and the history of prayer in the American church. I noticed that [many] tended to think things were authentic if they were spontaneous, emotional and messy—and I wondered why that was. It turns out to have a lot to do with the way the Puritans understood prayer.

I hope this book helps us believe a little more in a God whose love is wildly beyond what we can imagine—whose love erases dividing lines and casts out all fears.

I think my readers will be most surprised by what I learned about purity and modesty—two virtues that have, in the church in the last few decades, been made to be primarily about women’s bodies and sexuality. But, in fact, in the Bible these virtues have very little to do with sexuality. What I found as I explored is freeing—and, in some ways, more demanding.

What do you see as the role that the faithful can play in bringing about change and increasing virtue in the world?

Lutherans have a wonderful heritage of reformation, and I believe that we must be always reforming our understanding of embodied goodness. … In this book, I don’t seek to offer definitive answers about what virtue is. I seek to model a way of engaging with your own life story and cultural context and Scripture with compassion and wisdom and openness to new ideas from new places. The virtues don’t change, but they do look different [for each person]—your task is to learn how to embody them best in your life.

Hope is such a vibrant thread in the book. What is giving you hope now, and what hopes do you have for your readers?

Last year, I had a group of college students that met at my house on a regular basis for soup and bread. All of them had been wounded by Christians—some of them had been rejected by their own Christian families. But every time they came to my house, they exuded joy; they discussed ways to communicate with people who didn’t understand them (or even try to understand them); they continued to love a God who seemed confusing and whose name had been used to hurt them. They give me hope. And so do my own children, and the young people at their school who are engaged in climate change activism.

For those readers who have been confused as to why so many young people are angry at the church, I hope this book helps them understand the anger. For those who have been hurt by religious people weaponizing “virtues” language, I hope this book helps them feel less alone, and helps them see that the gospel is not a weapon. And for all of us, I hope this book helps us believe a little more in a God whose love is wildly beyond what we can imagine—whose love erases dividing lines and casts out all fears.