In the past 10 months, we’ve seen the rise of “virtual church.” It’s important to note that “virtual” implies an approximation of the real thing. I host a podcast called the Vinyl Preacher; committed audiophiles are all too happy to tell you that the only way to fully reproduce the sound from the recording sessions for Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours (or any other album) is to play the vinyl.

When Rumours was released, the vinyl pressing preserved the analog sound of Stevie Nicks’ vocals and Lindsey Buckingham’s guitar. When that analog source recording is converted into a digital format, the sound is transformed into a series of ones and zeros. The higher the quality of the file, the more ones and zeros—but, eventually, that string of digits will stop. As in elementary school math, there’s often a remainder, and digital music simply rounds up.

Don’t get me wrong: I love digital music. I have a 1963 Westinghouse console stereo, but the vast majority of music I listen to is digital. We need to find a way for artists to be more fairly compensated for their streaming music―but as a consumer, I love it. And yet, it is always a compressed approximation of the real thing.

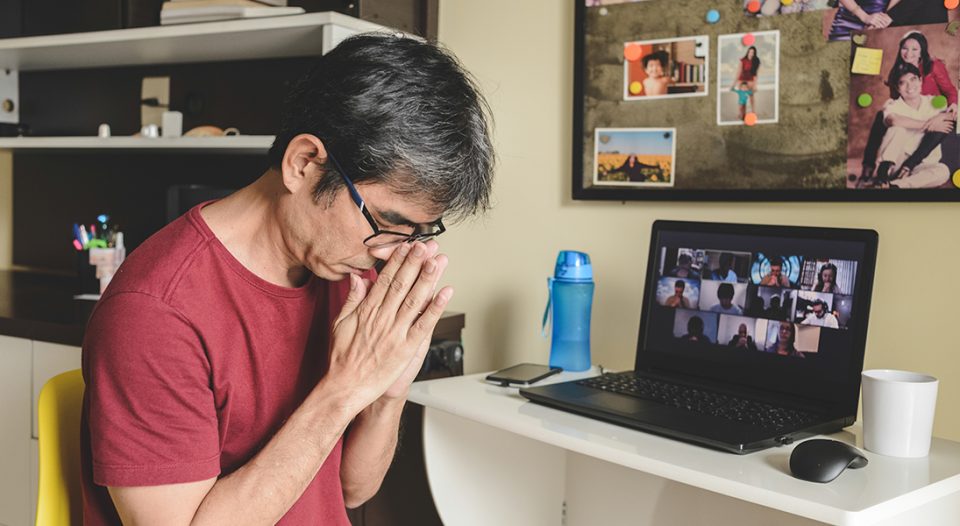

So, too, with the church. We can proclaim the word on Zoom or through FM transmitters in parking lots. We can pass out prepackaged and preconsecrated packets of crackers and wine. We can find ways to approximate all the ingredients of the liturgy and stream them out into the void, but the result will be, at best, a really good mp3 file. No matter how well we do this, it won’t be the real thing.

Matthew 16:18 is the first time Jesus uses the word “church.”

In Matthew 16:18, Jesus proclaims that Peter is the rock on which he will build his church. This is the first time Jesus uses the word “church.” The Greek word is ekklesia, “out from the walls.”

These days, what I miss most about church is the conversations I didn’t really want to have. The truth is that church is the only place where I’d voluntarily spend time with many of my neighbors.

In the ancient Near East, people’s only social responsibility was to their blood relations. This became a serious issue when a small grievance arose between families. There was no way to stop retributive justice. This dynamic of extreme commitment to one’s family often led to the destruction of entire families and communities.

The church was part of Jesus’ radical message, a call to walk outside the walls of your family’s home and establish a new family, to establish social responsibility both to and for the other, bound not by family, genetics or race but by our common humanity.

New walls

These days, there’s much online chatter about how, in the future, church will be “in the home.” Personally, after 10 months stuck inside with my loving family, I want nothing more than to escape. The church Jesus calls us to join always connects to, and builds social responsibility with, the other.

Some say digital church has provided a revolutionary way to connect with people across the physical boundaries that have historically stood between us. The dream of the internet was that all humanity might be accessible and connected, that it would tear down the walls that separate us.

Yet it’s clearer than ever that this dream hasn’t been realized. The algorithms that govern the social platforms of our day first connect us to those with whom we already agree. These algorithms also discreetly build new walls around these communities, whose respective members are as committed to one another as the ancients were to their blood relatives.

The algorithms that govern the social platforms of our day first connect us to those with whom we already agree.

More sinister, the algorithms ensure that the walls surrounding these communities are bordered by opposing communities, the people with whom we would have the most difficulty reconciling. Wars that never end increase the amount of time we spend on their platforms, scrolling, clicking and scoffing. The church that embeds itself in this reality is no more than a chapel inside the walls of a family compound in the ancient Near East.

The good news is that there are people out there who are not like you. There are people in the world with whom you disagree but can maintain a level of social responsibility.

The bad news is that, right now, we can’t find them. We can’t be with them. The bad news is that, right now, we can’t fully be the church. Until the day we can hold hands in prayer, until the day we can shake a stranger’s hand and pass a cup of wine, we will not be able to fully live into the vision of life together that God holds for us.

But that’s OK. It’s OK that we are not currently what we ought to be, because who we are now is who we have always been. We can and should mourn that reality. Yet, the church God has given us in our homes, online or in parking lots is enough to get us through until the day we can again squirm to get out of socially awkward conversations at coffee hour.