Editor’s note: This article is from the introduction to Death by Baptism: Sacramental Liberation in a Culture of Fear by Frank G. Honeycutt (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2021). Reprinted by permission.

As a Lutheran pastor for over three decades, I’ve led many church classes inviting participants to offer various images that come to mind upon hearing the word baptism. Groups suggest valid and biblical responses: new life, rebirth, cleansing, forgiveness, family, body of Christ.

However, the word death—a central reality describing the sacrament in the New Testament—rarely receives mention:

Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life. For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his (Romans 6:3–5).

St. Paul’s rather jarring declaration is no biblical anomaly: “You have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God” (Colossians 3:3); “When you were buried with him in baptism, you were also raised with him through faith in the power of God” (Colossians 12:2); “I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me” (Galatians 2:19-20).

The Red Sea story in Exodus became symbolic of how baptism drowns the pursuit of sin and the old life in Egypt, washing up a new community of people on the far shore of a whole new land.

Elaborate sermons on dying in baptism were once preached in the early church. The Red Sea story in Exodus became symbolic of how baptism drowns the pursuit of sin and the old life in Egypt, washing up a new community of people on the far shore of a whole new land.

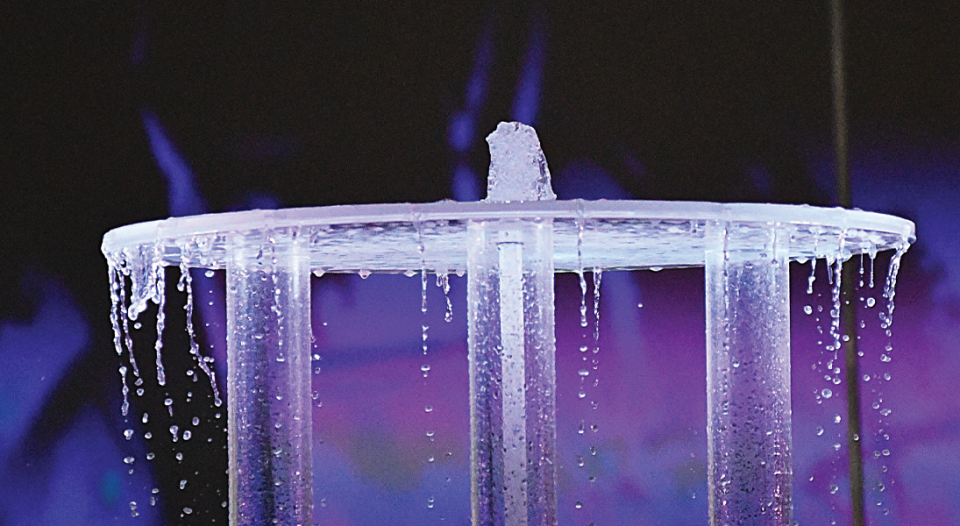

Popular at one time in church history was a tomb-like function for baptismal fonts. Catechumens baptized in the font of St. Ambrose (340-97) in Milan descended precipitous steps into water with depth, dying into Christ’s body (the church), and ascended steps out the other side to a waiting congregation and first communion. Martin Luther preferred full immersion in the waters of the font, even with small children, to suggest a visual dying and rising with Christ—a drowning, a death, a new creation. This liquid drenching is in rather stark contrast to the minimal use of water in many churches today in what has been whimsically called a “dry cleaning.”

The connection between death and baptism is rather murky in much of the church today. That baby is just too cute! So full of life and curls and dimples. Innocence clouds our thinking. The sacrament often becomes more about family tradition, photo opportunities, and even a fuzzy and misguided notion of fire insurance, a magical protection from a hellish afterlife. I’ve received more than a few frantic phone calls from mothers who ask, “Will you do my baby?”

Desiring to maintain evangelical inclusion, pastorally raising the connection between death and baptism is a challenge under such circumstances without scaring away a prospective member of the congregation.

The connection between death and baptism is rather murky in much of the church today.

In many parts of Central America (a region where death and violence are daily realities), the priest and other family members somberly process into a darkened nave wearing funeral garb as worshipers intone songs of lament and loss. At the altar, the priest plunges the naked child completely underwater into a wooden font shaped like a funeral casket and says, “I kill you in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit … and raise you to walk in Christ’s light and love forever!”

Post-baptism, the congregation dramatically shifts to songs of Easter praise. The dripping-wet child is garbed with a white baptismal gown and screams like she’s just been born—an apt image. Try this just once in your home congregation and somebody will call the Department of Social Services.

To our great theological impoverishment, the church has largely lost the core image of dying with Christ in celebrating the sacrament of baptism. St. Paul uses the word death (or its close cousins) 14 times in the first 11 verses of Romans 6.

I counted.

Baptism is not some holy inoculation protecting disciples from evil and mishap. Jesus proceeds directly from his baptism in the Jordan River, barely toweled off, to an immediate encounter with the devil in the wilderness (Mark 1:9-13). Apparently, this ancient sacrament fails to magically protect Jesus or his followers, chosen recipients of God’s promises, from whatever’s “out there.”

Baptism instead provides the church with the spiritual wherewithal to confront and talk back to sin and evil. Dying with Christ in baptism suggests a powerful truth: nothing can “get” us—God’s already got us.