It is not unusual for a business or significant corporation to rebrand. Just recently, Augsburg Fortress changed its name to 1517 Media. Seven years ago, the ELCA Board of Pensions rebranded itself as Portico Benefit Services. When rebranding occurs, it often succeeds in polishing the corporate image.

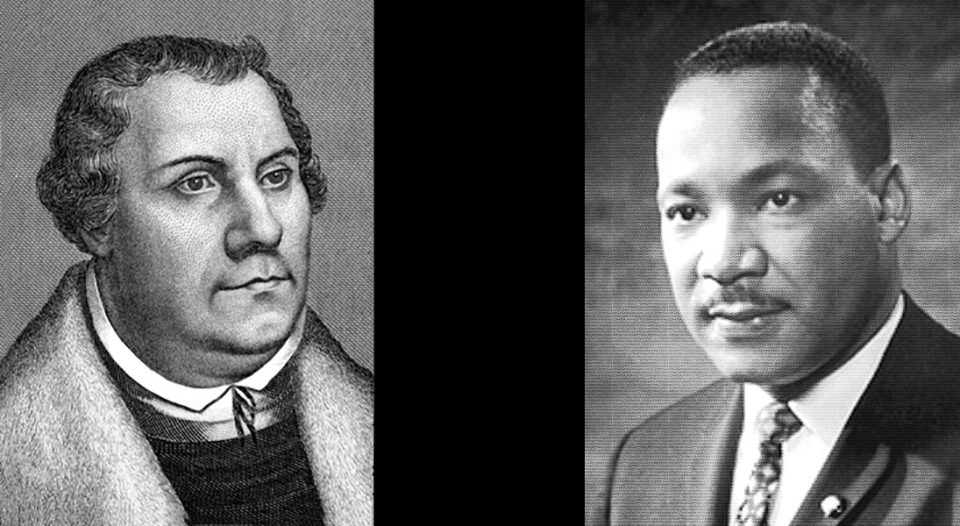

Michael King Jr. was born Jan. 15, 1929, in Atlanta, the second child and firstborn son to Michael King Sr. and Alberta Williams King. As author Taylor Branch depicts in Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63, when Michael Jr. was young, Michael Sr. was a member of a worldwide delegation of Baptist ministers touring Jerusalem and Palestine. The trip debriefing took place at the Baptist World Alliance conference in Berlin. During this time, King Sr. visited many of the historical sites in which a German reformer by the name of Martin Luther took his volatile stand against the indulgence abuses of the Roman Catholic Church.

Branch wrote that King Sr. had had an epiphany of sorts during his journey, and when he returned to Atlanta—to much fanfare, thanks to his increasing prominence and affluence as pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church—he began to identify with a name that would classify him as a reformer, in Atlanta and beyond. In place of both his and his young son Michael’s names, King began using one befitting a reformer: Martin Luther.

The process of changing his name was a gradual one. As Branch points out, in religious history, name changes are a witness to denote the existence of a new person; God often did the rebranding, or indeed, renaming. Abram became Abraham; Sarai, Sarah; Jacob, Israel; and Saul, Paul. The disciple Peter got rebranded by Jesus Christ himself. In his 1980 autobiography, King Sr. states that the change caused a contentious debate between his parents. His mother’s preference was the name Michael, given after the archangel.

Luther was a reformer whom King felt embodied the prophetic discernment of his future work and social change.

We don’t know how much influence the Protestant reformer had on King Sr., but based on King’s activism through his ministry in Atlanta, I believe that he identified with Luther. After returning from Europe in 1934, he rarely referred to himself as Michael King, typically using Martin Luther King or M.L. King.

While King Jr. began going by Martin Luther at age 5, legally his name change was not complete until July 23, 1957. What would cause him to legally change his name to Martin Luther King Jr. in 1957—after his successful Montgomery bus boycott and before his trip to India in 1959? This was a deliberate decision to formally identify with the most famous reformer in his historical and theological studies. Luther was a reformer whom King felt embodied the prophetic discernment of his future work and social change.

King’s rebranding in the Spirit took shape, in part, by challenging in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” the “white moderates” who straddled the fence of being an apathetic spectator or an active participant in the unfolding drama of liberating action and revolutionary ferment. His rebranded life in the Spirit culminated when he began to speak out vociferously against the Vietnam War and poverty. Like his namesake, he addressed the cultural forces of his day—racism, classism, militarism, consumerism, nihilism, fatalism and a general chaos and disintegration.

When an assassin’s bullet shattered his jaw in the midst of working for economic justice, the man who became Martin Luther King Jr. could say, as found in the expressions of his enslaved ancestors, “I know I’ve been changed / The angels in heaven done signed my name.”