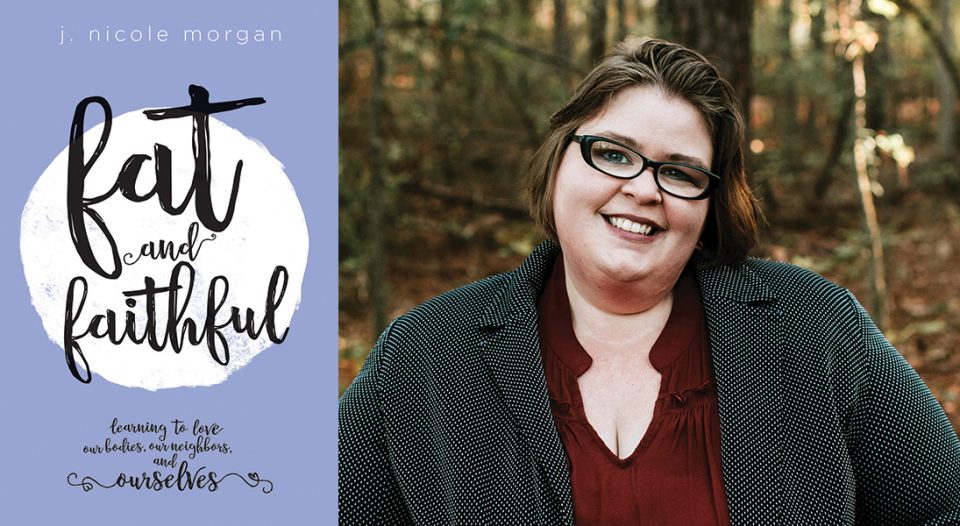

As Lutherans, we know our faith is an embodied one; our bodies are intentional and good. But in an image-focused, calorie-counting world, it’s possible to forget that each body is worthy and has dignity. As people of God, it’s important to question our own biases as we learn to love our neighbors better. J. Nicole Morgan’s new book, Fat and Faithful: Learning to Love Our Bodies, Our Neighbors, and Ourselves (Fortress Press), is an invitation to that self-examination for both individuals and congregations.

Living Lutheran spoke with Morgan about body shame, bias and learning to see the image of God in every body.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell us about Fat and Faithful?

Morgan: My book is a little bit memoir, a little bit theology. It tells different stories from my life as a fat Christian, and it also looks at the theology of bodies and what it means to be an embodied human made in the image of God and who the Holy Spirit indwells. How does that show up in fat bodies? What do fat bodies teach us about the image of God? How do we honor fat bodies as members of our community and as part of our call to love God and to love neighbors?

My book is about bodies and our own self-image, but I think it’s more about community and what we can do as Christians to make sure that we are opening our doors and making spaces at tables, literally and figuratively, so there is space for everyone to be there and to contribute.

Many people may be unaware of fat bias in the world, perhaps especially in our churches. Will you talk a bit about your experience with that bias?

If I show up at a [doctor’s appointment], no matter what my complaint is, the likelihood that they will just tell me to lose weight is high. I’m very intentional now to look for a doctor who will take blood work and listen to what I’m saying and actually treat what’s happening. There are other studies that talk about how fat people are less likely to get jobs or advancements. It’s harder to get adoptions and housing.

In the church, specifically, where I focused most of what my book is talking about, fatness is often seen as a sin, or as a sign of a sin, depending on who is talking. [It’s] this idea that thin bodies represent self-control and self-control is a fruit of the Spirit. So if you were fat, you didn’t have self-control, which meant you didn’t have the Holy Spirit, which meant you weren’t a Christian, or weren’t a good Christian, or there was some kind of major sin in your life.

In your book, you share what you’ve learned about the intentionality of your body and how that is important to the way you experience your faith. Would you talk about that?

For most of my childhood and young adulthood, there was this idea that my body was what was wrong with me—that maybe I could love God, and maybe I could figure out how to be a Christian, but my body was a stumbling block or an obstacle to fully experiencing that. As I came to understand, and as I studied Scripture, theology and embodiment, I really looked into this idea that everyone is created in the image of God. If we are all created in the image of God, then each of us reveals something about God to the rest of the world.

If we are all created in the image of God, then each of us reveals something about God to the rest of the world.

I started asking, “What does my body teach me about God or reveal about God?” And the first one that stuck out to me is that I am warm and comforting and soft. I am a welcoming and safe space for people who need comfort and rest, and that is part of who God is. When we ignore the visible representation of that warmth and comfort, we can lose seeing that as a priority for our church as a whole, for that communal body of God.

Also, my body is very steadfast—it’s hard to move me. I can stand in a place and people can’t push me off of that place. That’s also a part of the heart of God to be steadfast. Thin bodies show different things, and being able to see that collective picture of God, I see the various characteristics and nuances and symbolism that shows up in all of these images of God around us. I think it’s a beautiful thing. My body is not an obstacle—it adds to my faith and to the faith of those around me.

Your book addresses the biblical concept of gluttony, which is often wrongly associated with fat people. Could you tell us a bit about what gluttony actually is?

Gluttony is consumption at the expense of others, especially the marginalized. I use a couple of different stories from the Bible to talk about that, but if you go back and look at the Bible, [the] people who consume resources who are accused of gluttony are consuming in a way that doesn’t take into consideration the needs of the people around them. That is a sin that people can struggle with no matter their size. Every instance of feasting in the Bible is certainly not gluttony. God ordains feasting and God encourages us to eat together—that’s part of how we do community.

Inclusion can often be as basic as making sure accessible seating options are available—but it doesn’t stop there, of course. What are other ways congregations can make their spaces and events more welcoming?

I am a big fan of just asking. You don’t have to ask specifically about size, but having some kind of method [for] your church or community makes it easy for people to let you know if they can’t access it and to suggest options. Be proactive as much as you can. My book tells you to make sure you have a variety of seating, so go ahead and do that, even if no one asks. There are so many needs that might be specific to people. Create a culture where it’s OK to name your own needs. … Saying, “If you have barriers, please let us know—here’s the email, the phone number, the name of the person to ask for,” that’s one way of creating that culture.

I always try to tell people if you have any kind of shared clothing make sure that it comes in a wide range of sizes: choir robes, assisting minister robes, camp T-shirts—be very intentional about the sizing and know that 2X is not a magic size that expands to fit everyone.

Do you have suggestions for those seeking to be affirming of people of every size?

This is a really tricky one, partly because not every fat person is going to want you to affirm their size; it’s still a very sensitive issue. You honor people the way you honor everyone else: ask them if they are comfortable. … [Not everyone is] great at naming that, and you do run the chance of offending people when you’re talking about body size, so definitely be sensitive there.

What are you hoping for your readers as you send your book into the world?

I’m really hoping it’s a start, a new way of thinking, where people come to believe that God loves and accepts them and their bodies just as they are—that they are fully equipped and capable to serve God and to love God and to love neighbors in the bodies that they have—and they don’t have to “fix” their bodies before they can start that.