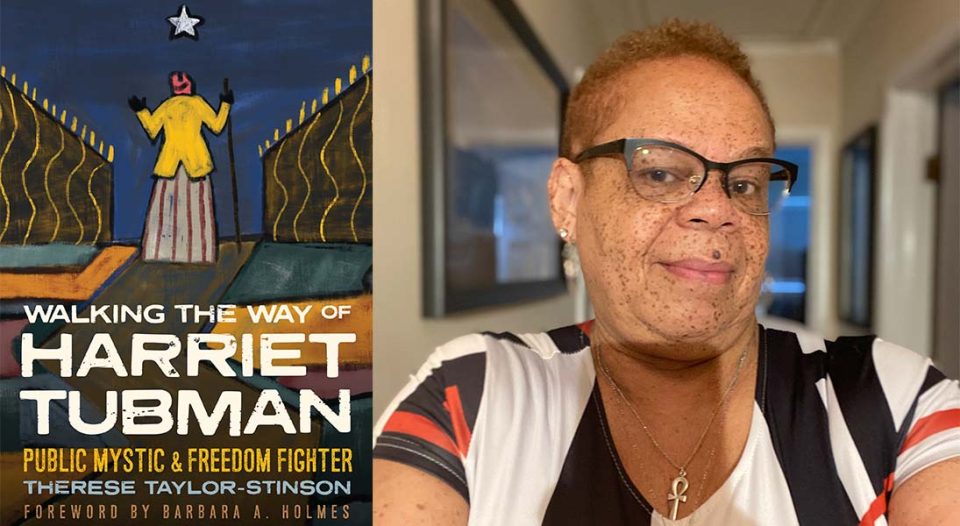

In her new book Walking the Way of Harriet Tubman: Public Mystic & Freedom Fighter (Broadleaf Books, 2023), Therese Taylor-Stinson examines an aspect of the iconic Underground Railroad leader that’s not typically a focus of Tubman’s biographies: her spiritual life. Taylor-Stinson, a deacon and ruling elder in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), uses the lens of Tubman’s deep faith to offer readers a path for their own lived spirituality.

Living Lutheran spoke with Taylor-Stinson about the pursuit of internal freedom, faith-informed activism and her ministry as a spiritual director.

Living Lutheran: How did you decide to write Walking the Way of Harriet Tubman?

Taylor-Stinson: Barbara Holmes talks in her book Joy Unspeakable (Fortress Press, 2017) about public mystics. I know from being a person of color and an African American—particularly, I know more about the African American church than, broadly, churches of color—that, usually, someone might be identified a mystic, but it was something that was whispered. It wasn’t really something that was said out loud. I know that the Black Catholic churches always lifted up certain persons of color as being mystics or figures that should be given a different status, as the Catholic Church does. But generally that doesn’t happen where Black people are named. [Something] I saw in Harriet is that the things she was doing and how she even transformed her handicaps [such as her traumatic brain injury-induced narcolepsy] into things that were able to help her and her deep faith in God, certainly that, to me, identified her as a mystic.

Harriet’s [grandparents] were from Africa, they came through the Middle Passage. So Harriet’s only two generations away from the Africans. I’m assuming that even if she was born here, the family members and community around her were people who were still connected to those belief systems. So one of the things I did was to find something that I could read about mysticism, particularly in Indigenous cultures. I also found in this article that … in terms of African mysticism, in their belief system, the gifts that you are given from a supreme being … are for your community. Harriet Tubman basically gave over her life to her community.

Now, I also have an attachment to Howard Thurman. … In Jesus and the Disinherited, [he wrote] about finding the genuine in yourself and, speaking in different terms, about internalized freedom. When I look at Harriet’s life story, she had to have that. How can you step in front of a 2-pound weight and be struck in the head and it caused you some kind of a disability that you’re able to actually transform into something helping you make those journeys? And she’s the only person who made those journeys and was not caught. …

So it was important to me to unpack her story in terms of her spiritualty and how it conforms with the information that I read about African mysticism.

That’s what happens in mysticism, that you become aware of something that’s greater than all of us and how that connects to who you genuinely are.

How do you define “public mystic”?

A public mystic is someone who gives themselves to their community. They have a relationship with a higher power or the cosmos or the divine, or however you want to call that. They have that relationship that helps them. You know, Jesus said love your neighbor as yourself, and most of us have forgotten all about “love yourself.” We do all these things thinking we’re loving our neighbor, but the first thing you have to do is be on the right path yourself, right? So I think that that’s what happens in mysticism, that you become aware of something that’s greater than all of us and how that connects to who you genuinely are.

So that’s the mystical part. But what makes it a public mystic is that, with many of the mystics, we read about their writing things and their being held up, but you don’t necessarily see them making any difference in the public square, where public mystics are helping their communities. Which is very much an African idea, where not only do you give to your community, but your community actually also helps you define what your gifts are, who you are. It’s ubuntu—“I am because we are.”

Many readers are familiar with Tubman as an abolitionist, but less so with her spirituality. How did it shape her activism?

One of the things that I learned in my reading was that Harriet Tubman had a specific kind of narcolepsy that didn’t necessarily put her to sleep but put her in a trancelike state where she would have dreams. And this may have [been] because her brain was thinking about this, but her dreams always had something to do with how she was going to accomplish getting her charges to freedom.

Sometimes they would be [walking] along the path … and then, all of a sudden, she would have one of her narcoleptic episodes that would put her into a dreamlike state—not really sleep so much—and in that dreamlike state, she would somehow get messages: “Don’t go in that direction, go in this direction.” So she would wake up, and they would be frightened: “What’s happening? You’re sleeping when we need to be running away!” And she would say, “Don’t go that way, go this way.” And these were messages she believed came from something greater than her, what she would call God.

And she was learning as she went along. By the time she got to Philadelphia, I’m not sure if that’s her first encounter with Frederick Douglass or not, but they become close friends. So she’s learning from him. And then eventually she goes further north, where the abolitionists are. And many of the white women in the women’s suffrage movement at the time were informing her of the way they were confined in their way of being because they were women. And Harriet Tubman was acknowledging that not only were they confined in that way, but she was finding herself, even in her role, somewhat confined in that way, but even more because she was a Black woman.

She is not only concerned about taking Black people to freedom but also she’s seeing that freedom is more than just a physical location.

I call her the first womanist theologian as well, because she said, because of that, she is not only concerned about taking Black people to freedom but also she’s seeing that freedom is more than just a physical location. This is something that she’s learning from her travels. All of those things develop, one on top of the other, to get her charges to someplace where they can think they’re free anyway. But it also widens or broadens her perspective of just what freedom is. And I think that’s something that, even today in the 21st century, we’re still trying to figure out.

You include practices for readers at the end of each chapter. Did your work as a spiritual director—and as the founding managing member of the Spiritual Directors of Color Network—inform that approach?

Absolutely. Partly being a spiritual director, partly because, in being a spiritual director, I practice those practices. Tomorrow I’m going to be holding a centering prayer group. So I know those things have helped me to find myself—although it’s not always easy and there’s always people trying to put you back in the box they think you belong in. But they have been ways for me to keep hold of who I am and to be myself.

And some of it takes courage. One of the things I like about Jesus and the Disinherited (Abingdon-Cokesbury Press, 1949) the most is Thurman’s first chapter on Jesus because it shows that that’s exactly what Jesus did. He said, “This is who I am. So in spite of [being] part of these marginalized people over here or whatever they’re teaching up there in the Sanhedrin, I believe God is sending me in this direction.” And unfortunately, it got him killed. Nevertheless, he did make a difference. He did something.

Which has made me also think about when negative things happen. … In the midst of that, how do you live through these things, other than finding who you really are and how these things inform the genuine in you and your path in this life?

What do you most hope readers will take away from the book?

I hope that they will become aware of their own life in a way that makes them want to serve. A lot of times what we do is, we think we know who we are, or we make ourselves who the dominant culture says we should be, and then we lock ourselves in that box and just try to get through life. And I’m hoping that reading about Harriet, and even reading part of my story, which is in [the book], or just the challenge that I wrote such a book will make people want to do likewise and to expand their understanding of themselves and to look for the genuine in themselves. Even small things can turn into big things when we are doing them.

I think, at first, Harriet was really just trying to get to freedom so that she could be free, go back and get her husband, and they could have children that weren’t confined to enslavement. But that story didn’t go quite like she wanted it to, and that just led her to something else, and [then] something else. And then her whole life became this desire to free others, which she believed God had given her the access to do.