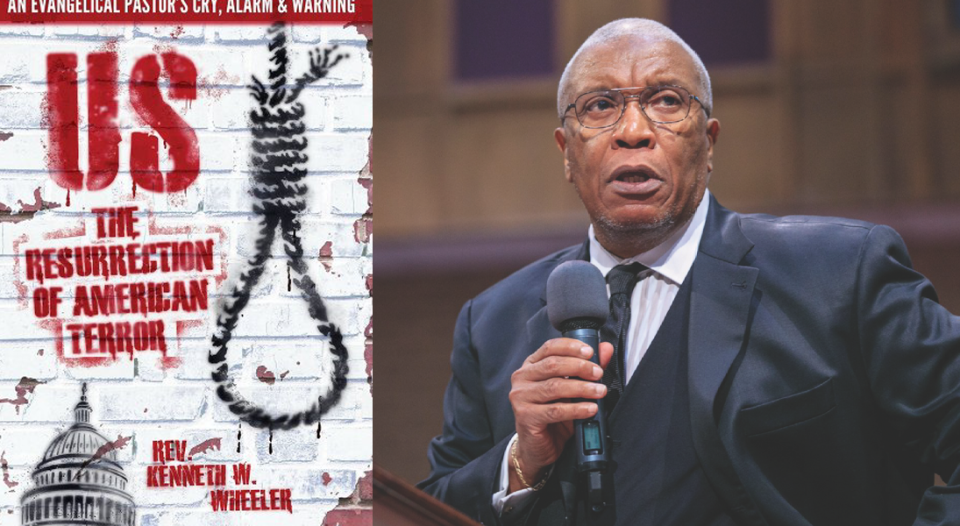

Kenneth Wheeler was compelled to write his new book US: The Resurrection of American Terror (Precocity Press, 2022) after connecting the trauma he’d experienced under Jim Crow segregation to the rise in Christian nationalism he’d seen in recent years. A retired ELCA pastor who served the Greater Milwaukee Synod for 18 years as an assistant to the bishop, Wheeler decided to draw on his experience as a Black pastor in predominantly white church spaces to write this book.

Grounded in Scripture, US challenges readers to reclaim the fullness of their humanity. Living Lutheran spoke with Wheeler about the vulnerability and directness needed to write such a book.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell readers about US: The Resurrection of American Terror?

Wheeler: This is a book, first of all, about me growing up in the Jim Crow South in the 1950s and ’60s. I lived in that ugly reality for 17 years, until I went away to college. I thought it important to start with the personal impact that living under this evil system had upon me. This was a “setting the stage,” so to speak.

But a large part of the book is about the institutional and systemic dimension of white supremacy and how white supremacy has touched and influenced our national and religious life. I wanted to speak particularly about how I experienced life in a predominantly white denomination as a Black man and as a Black pastor. I wanted to speak about the pain of that as well as the injustice of it.

How did you decide to write the book?

I think that I had been carrying this book inside of me for a long time. A lot of the historical [aspects] I had researched and kept notes on over the years. My own life experiences, beginning at a young age, with the virulence of racism, I had stored in my mind. I thought that is where they would stay, because many of them were painful. I was fortunate to have an editor who pushed me to take those stories from my mental vault and write about them. “Those stories,” she would remind me often, “are what has made you who you are. You need to tell those stories for yourself, and you need to tell them for those who will read your book.”

Since the book’s publication, I have received a great number of correspondences from people across the country and across the ELCA expressing their appreciation for my vulnerability and my commitment to speaking truth.

I had been carrying this book inside of me for a long time.

Ultimately, I wrote this book because … the rise of Christian nationalism was … offensive to me and stood as a contradiction to the gospel of Jesus Christ. I had come to the realization that both white supremacy and racism were the greatest existential threats to our nation and to the white church.

You write about the ways predominantly white churches have centered a “white version of Jesus.” Could you speak to that?

This goes all the way back to slavery, when white slave owners used the Bible to support this evil institution. One African American theologian said that the most egregious act of white supremacy was the colonization of God.

It is my belief that the only way white Christians could assuage their consciences around slavery was to make God a willing participant in this thing that was known as America’s “peculiar institution.” In truth God would never have condoned such an institution as slavery. He would never have sanctioned such evil. But white supremacy would, and white supremacy had become America’s god.

What do you believe it would look like for church members to reject and repent of white supremacy?

The ELCA adopted and passed a resolution condemning white supremacy. We did this on a churchwide level, but the meaning of this has not gotten into the church’s bones, nor has the meaning contained in those resolutions trickled down into local congregations. Repentance not only requires the ELCA to renounce white supremacy but to remove every policy, every system that keeps putting its knee on the necks of people of color.

It would mean opening up the call process and bringing the names of candidates of color without hesitation to predominantly white congregations. It would mean that every white congregation would commit to yearly anti-racism training, and that no white congregation could opt out of such training. It would mean that white clergy who preach about race in their congregations will not be penalized by their congregations or their bishops.

How do you hope readers engage with the book?

I am grateful that so many people are reading this book. … I have been overwhelmed and humbled by the response. I would ask the reader this question: What will you do with what you have just read? How will you act? Will you talk with others in your circle about the book?

To learn more about the ELCA’s racial justice ministries, visit elca.org/racialjustice and elca.org/racialjusticepledge.