How can predominately white churches engage in the necessary preparatory work to call ministers of color to lead them? Leaders of color in the ELCA often face discouragement and lack of support. According to “God’s faithfulness on the journey,” the ELCA rostered women of color project, women of color in the ELCA wait three to five years to enter their first pastor calls, and 45% report receiving compensation below synod guidelines.

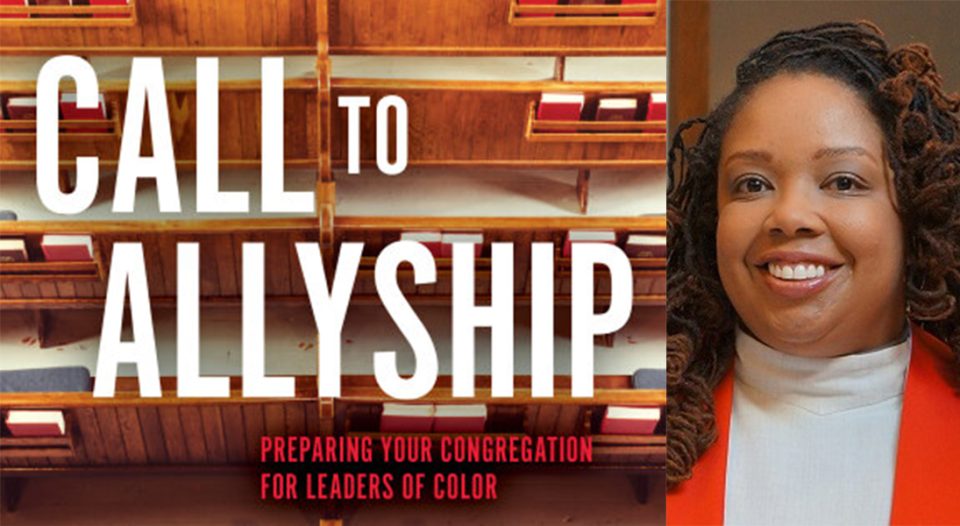

In the new book Call to Allyship: Preparing Your Congregation for Leaders of Color, editor Angela T. !Khabeb and a variety of ELCA leaders of color (Kelly Sherman-Conroy, Patricia Davenport, Jenny Sung, Priscilla Paris-Austin, Viviane Thomas-Breitfeld, Andrea Walker and Felix Malpica) offer personal stories, hard truths and practical tips for how churches can effectively ally themselves with the leaders they call.

Living Lutheran spoke with !Khabeb about Call to Allyship, part of Augsburg Fortress’ new “Mouth House” book series. Inspired by Martin Luther’s declaration that “the church is a mouth house, not a pen house,” the series aims to move readers beyond the written word into deeper conversation and meaningful action in their communities.

Living Lutheran: How did the idea for Call to Allyship originate?

!Khabeb: My dear colleague and friend Dawn Rundman at 1517 Media was developing a new book series for Augsburg Fortress that eventually became “Mouth House.” Dawn wanted the first release to include a book about how predominately white churches could prepare for calling a leader of color. She knew I enjoyed writing for ELCA audiences and understood that I had a wide span of contacts of ELCA leaders of color. She believed it was essential that this book was edited and guided by a leader of color with this expertise and these contacts. That was the beginning.

How did you decide on the contributors and topics included?

Last fall Dawn and I talked through potential chapter topics, and the table of contents took shape rather quickly. We talked about various topics like intersectionality, the call process, compensation and leaders’ families. Some of the other chapters’ topics emerged after our slate of authors solidified.

How did you and the authors decide on a balance of sharing both your personal experiences and tips for congregations’ next steps?

I invited the authors to speak freely and assured them that their candor, wisdom and voice are what was needed for this project. The balance of sharing personal experiences and insights for next steps seemed to unfold quite naturally. I suppose it’s second nature due to most of the writers’ lived experiences—that is to say, daily dealing with many microaggressions while ministering to the body of Christ. Consequently, living out this balance is par for the course.

Throughout their writing process, we let [the authors] know that the first goal of this book series was to not cause harm. For some authors, myself included, revisiting past trauma proved to be overwhelming at times. I found myself reliving the pain. We encouraged the authors to take a break in their writing if needed, and also let them know that they did not need to include anything about their personal experiences that was too difficult or painful.

What’s most important is that we understand that everyone can do something. Every congregation can take steps.

This is a work of the heart and soul. I hope that people will return to these chapters again and again, because I think many of the tips are going to be relevant during different times of the call process and if individuals and churches are seeking ways to become more deliberate and effective as they answer the call to allyship.

In the book you write about the distinctions of homework, hands-work and heart-work. Although those will look different for different readers’ contexts, could you share about what that work entails?

Homework, hands-work and heart-work are fluid groupings that may be broadly defined. I offer these three avenues so that everyone can begin somewhere. Even if a congregation is not ready to call a leader of color, there are activities in which to engage for both individuals and/or the larger worshiping community.

In general, homework refers to activity that a congregation can do collectively. It can be as simple as a book study or as deeply involved as a racial justice audit of the congregation. Hands-work speaks to concrete action that can happen within or beyond the congregation. For example, volunteering at a BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, people of color]-led ministry or dedicating a reparations fund as a line item in your congregation’s annual budget. Lastly, heart-work encourages us to maintain an open posture to the activity of the Holy Spirit so that we are transformed by the renewing of our minds, [as we read in] Romans 12:2.

What’s most important is that we understand that everyone can do something. Every congregation can take steps. Get creative and keep Christ at the center of your actions! [As Isaiah 43:19 says,] “Behold, God is doing a new thing. Do you not perceive it?”

Call to Allyship largely concerns ELCA congregations and members. But much of it is also applicable to other predominately white churches and spaces. How do you hope readers will engage with the book?

The first chapter invites people to engage this book in community. For example, church councils, call committees or racial justice teams can read the book together and take time as they read to really consider what each author is saying. In fact, I think the whole congregation could benefit from reading it.

Call to Allyship reaches beyond Lutheran communities. We are hopeful that readers outside the ELCA will resonate with this book as well. While there are some parts of the call process that are specific to our denomination, any predominantly white denomination that is seeking to equip its congregations to call leaders of color could benefit from virtually all of its contents.

Ultimately, this book is meant for everyone. This book is meant for all who long to live in beloved community, as described by Dr. Martin Luther King. It is meant for everyone who is called through baptismal waters to work for justice. Remember, beloveds, we serve the God of transformation, and we are God’s children. Transformation is necessary—and continuous. It is my hope that a spark will be kindled within the reader, and the Spirit will continue God’s sacred transforming work throughout the body of Christ.