In 1961, Kyuzo Miyaishi arrived in the United States to attend Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary in Columbia, S.C. Born in Tokyo to a Buddhist family, Miyaishi fought in World War II and was struggling with suicidal depression in postwar Japan when he met an American missionary who would dramatically change the course of his life.

After converting to Christianity, Miyaishi—who became better known as Frankie San—enrolled in seminary and, after graduating in 1966, was ordained as a Lutheran pastor. He spent the next five decades living out his faith through dedicated, active ministry to prison inmates in one of the most dangerous penitentiaries in the U.S., Central Correctional Institution (CCI) in Columbia.

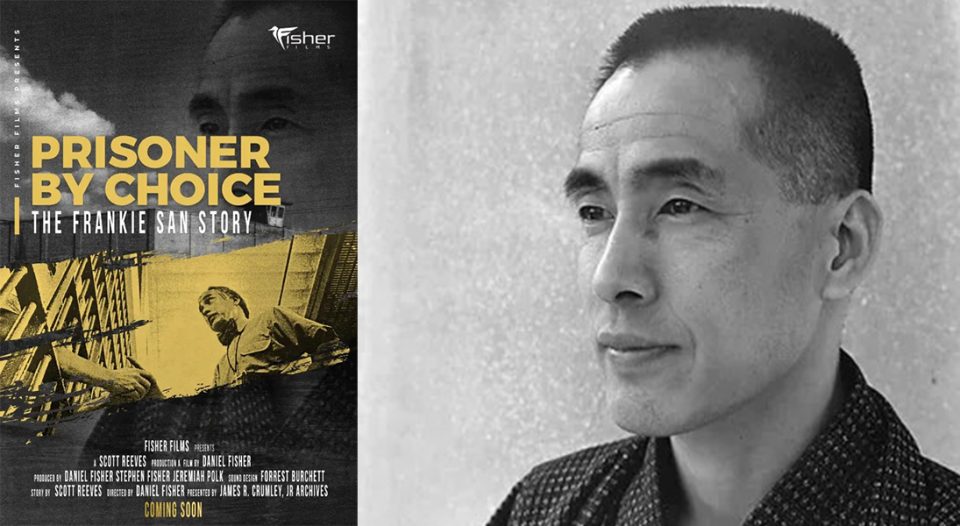

Last year Frankie San celebrated both his 94th birthday and the release of a new documentary about his life, Prisoner by Choice: The Frankie San Story. Living Lutheran spoke with Scott Reeves, executive producer and screenwriter of Prisoner by Choice, about the film and how his work as a church archivist and professor led to its creation.

Living Lutheran: First, could you tell us about your work as an assistant archivist with the James R. Crumley Jr. Archives for Region 9 of the ELCA?

Reeves: My work at the archives has included processing collections from various churches and institutions in the ELCA, serving patrons with research assistance, tracking the provenance and publishing research on a collection of books believed to be the first library collection for the Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary, and now producing film projects related to the archives and the collections found there. Since Prisoner by Choice, film work has become a significant part of my duties at the archives as we seek to use new methods to preserve the history.

Aside from that documentary we have produced a short web series introducing people to the archives and the collections found there, and we are currently working on a multipart film project seeking to preserve the unsung history of Black Lutherans in Region 9.

How did the idea for a documentary about Frankie San originate from that work?

One of the places in which I teach is an associate’s degree program in the South Carolina prison system. One summer I was teaching a class in the prison in the mornings and working in the archives in the afternoons. [I began] to process a collection of newsletters from a gentleman who went by the name Frankie San and had officially served as a minister to prisoners here in South Carolina from the late 1960s until 2013. As I skimmed through the stories in the letters, I found them to be incredibly interesting. The thought hit me that this would make a great story for a film.

The thought hit me that this would make a great story for a film.

I did ask my prison students about Frankie and learned that one of the guys, named Jimmy MacPhee, had actually known Frankie, corresponded with him for years and credited Frankie for his own coming to faith in Christ.

In the summer of 2021 … we received more documents for the Frankie San archives collection. As I started working on that, I mentioned to Shannon Smith—the director of the archives—that I thought his story would make a good film and was worth trying to preserve on film. She asked what it would take to do such a thing and proceeded to write for a grant to get our first film footage of Frankie, who was about 92 years old at that time. The grant was awarded and the process of making the film began shortly thereafter.

From there, how did the project come together?

The initial grant was really only enough to pay for a crew to shoot an interview with Frankie—who was now in the beginning stages of Alzheimer’s—and his primary caregiver, his friend and Jimmy MacPhee. … We didn’t know what else might come of that, but as I shared my excitement over a coffee with a friend who worked in PR and media, he told me he was working on a project to raise awareness about the positive effects of prison ministries on recidivism rates [and] asked if I could write up a proposal for such a project that would be built around Frankie’s story. I had not at that point worked in film in any official capacity, but I told him I could do it.

A good friend and former student of mine named Daniel Fisher had a growing local film company, Fisher Films. From time to time I would work with him on story ideas for small projects. Because I knew of Daniel’s work and worked well with him on story development, I asked if we could go with Fisher Films [for the] project. And since they were shooting the footage for the archives, we were able to arrange to share the film load, using footage of Frankie from the archives shoot for the ministry promotional project, and footage from that project to help with the Frankie documentary.

After those arrangements were made and the work on the promotional films was underway, we began looking into making our raw footage into an actual full-length documentary. Crumley Archives was willing to help raise funds to create the documentary, and Fisher Films agreed to take the risk of making the film, even if the full budget was not met. … The ownership of all raw footage and the completed documentary film will revert to the archives after a certain time to be preserved for posterity.

What made you want to tell Frankie San’s story—and tell it in this way?

Frankie’s story is compelling. It is the type of story that any storyteller would want to tell. When I first learned it, I would frequently bring people to tears in the telling of it. Once we completed the shorter project on prison ministry and recidivism—about a year before the completion of the full documentary—nearly everyone with whom I shared the first segment … wanted to hear and see more.

Why a film? Accessibility. … Statistically it has been shown that a significant portion of millennials and Gen Z get their information through documentary-style film presentations. So, in whatever way I can, I want to tell stories that introduce people to the true and good and beautiful stories that I find that communicate something of the love and grace of God. Frankie’s story does exactly that.

Frankie San served as a librarian, counselor and caregiver at CCI. What were some of the most remarkable things you learned about him in the process of making this film?

Frankie is a remarkable man, so it is difficult to narrow down an answer to a few things. He lived in an unused guardhouse of the old prison grounds [at CCI] for decades prior to that prison being shut down. He saw the prisoners who were trapped there as his people, and he gave practically everything to them—not just his money and time but himself. He is honestly one of the most generous people I have ever met.

He saw the prisoners who were trapped there as his people, and he gave practically everything to them.

One of his friends told of how Frankie always gave gifts to everyone when he visited their family. Another dear friend of his once wrote about how Frankie was a man with “no common sense.” I suppose such genuine selfless love can often seem like naivete to those of us in this rather jaded world. But Frankie was not naive. If I were going to sum him up, I would say he was a man with uncommon sense. He had the sensibility to really see people as beings made in the image of God. He had the uncommon sense to take Jesus at his word: “Just as you did it to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did it to me” [in Matthew 25:40].

What were some of the powerful moments for you that came in the making of the documentary?

Two of the most profound events related to the content of the documentary have to do with how we got many of the stories—events that to some would seem coincidental but that I would call providential.

One, that I was left to file Frankie’s newsletters at the same time that I was teaching prisoners and sensitive to the plight of such men. Two, that one of those men—Jimmy, so touched and transformed in part by Frankie’s life—would just happen to be in a class I was teaching when I first learned about Frankie. Three, that Jimmy, who was supposed to have [a sentence of] life without parole, was granted parole just at the time that we were finally able to pursue my desire to film this story.

Similarly, there is an unpublished book by a prisoner which we used in the film because it provided some insights not found in Frankie’s collection of stories and letters. That book practically dropped from heaven. Larry Tyree, a friend, caregiver and co-minister of Frankie, had found a small portion of this book written about the first prison where Frankie ministered. It had been dedicated to Frankie. When Larry first read what Frankie had of the book, nearly half of it was missing. Frankie had no clue where it was. Then one day while Larry was visiting, the ceiling over Frankie’s dining table collapsed due to a water leak—and that book in its entirety fell onto the dining room table in front of Larry.

You’ve made the film available to prisoners. How did that process work?

Making the film available to prisoners is connected to another one of those providential realities. My friend Dave, who asked me to write the series on prison ministry and recidivism, just happened to meet me for coffee the day after it was determined that we at the archives would get a grant to film Frankie. I was excitedly telling him Frankie’s story just days after he had been commissioned to do that prison ministry project. Furthermore, he works with a man, Bob M., who volunteers as a minister on death row. Bob knew Frankie—and it was his opinion that Frankie is “a legend” that inspired my friend to ask me to feature Frankie’s story in his project. Bob appears in the film.

I had wanted to try to get the film into the prisons but really didn’t know how to do so other than showing it to my classes and perhaps talking to prison chaplains. But before I could move on those efforts, Dave called me and asked if we would grant permission for the [South Carolina Department of Corrections] to load the film onto the tablets that were used by all the prisoners for communication with family and educational programs. Bob had already arranged for it, thanks to his ties with the state director of prisons.

Visit prisonerbychoice.com to watch a trailer and to order a DVD of the film, which is currently streaming for purchase on all major platforms and available for free with ads on YouTube and Tubi. Learn more on the film’s website, on Fisher Films’ Facebook page and on the Crumley Archives Facebook page.