Lectionary blog for March 3, 2019

Last Sunday of [time after] Epiphany

Exodus 34:29-35; Psalm 99;

2 Corinthians 3:12-4:2; Luke 9:28-36

The life of faith can be dull sometimes. Trying to be a faithful Christian, father and husband, I spend most of my time praying, looking for opportunities to serve, changing diapers, preparing meals and apologizing. This gets a bit repetitive. But every so often, God shines through with a word of shimmering life, an act of healing or just a moment that reveals one small piece of who God is and what God is doing in the world. Such moments make all the ordinary faithfulness worth it. Revelations of divine light in the bodies of Moses and Jesus must have been just such energizing moments for the people following them, respectively. But more than that, such revelation reminds us of our fallen nature and what God offers us in Jesus.

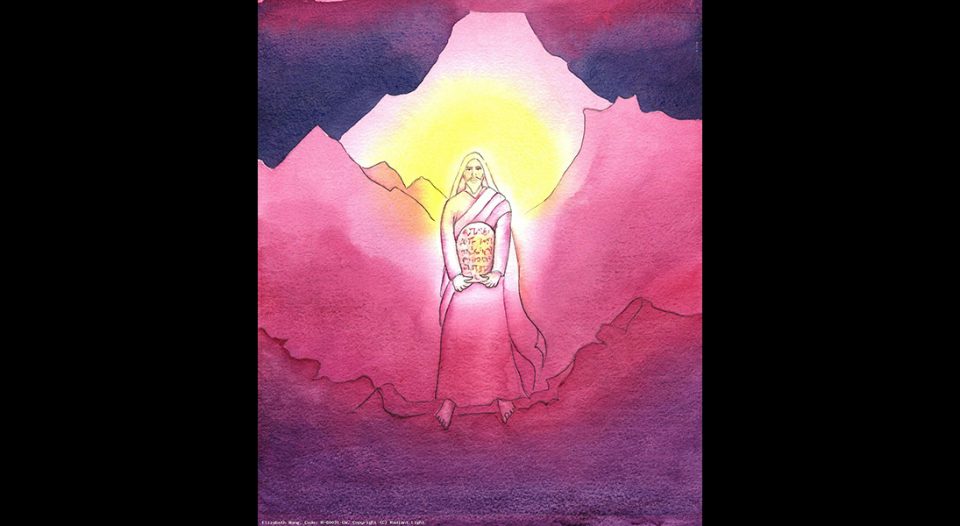

In Exodus, Moses climbs to the top of Mount Sinai and returns to the Israelites bringing God’s commandments, only to smash the stone tablets after witnessing their idolatry of the golden calf. He ascends the mountain again to beg for the Israelites’ lives and for God’s continued presence among them. He climbs the mountain a third time to assist God in creating a second set of tablets. When Moses finally came down from the mountain, his 80-year-old face is shining, not with sweat (as mine was the two times I climbed Jebel Musa in my 20s, stopping several times) but with divine light. Moses doesn’t realize that his face is shining (Exodus 34:29). But when Aaron and the rest of the people see him, they can’t bear to look at him unless he wears a veil to cover up the radiance.

The medieval French Jewish commentator Rashi points out how devastating the effects of the golden calf must have been: “Before the people began their sin, the text says ‘the appearance of God’s glory was like a consuming fire at the mountaintop, seen by all of Israel’ (24:17) and the people were not trembling or scared. But now, after the golden calf, fear grips the people and they tremble from the simple sight of the rays of light emerging from [Moses’ face]” (Rashi’s note on 34:30, my translation).

God had already relented from killing the people for their gross apostasy, and the new set of the law would have signaled God’s willingness to start over. But the people couldn’t let go of their shame and guilt based on their previous actions, so not only did they no longer cast their eyes toward God, they no longer even wished to see the face of God’s prophet.

At first glance, the text seems to imply that Moses complies with their wishes and covers his face. Instead, he insists that the people behold his face as he speaks with them! Moses took off his veil when he spoke with God (34:34). Then he made sure that when he was speaking to the people on God’s behalf, they could see his face—unveiled (34:32-33, 35).

God has done the difficult work in removing the powers of sin and death. All we need to do is be bold as we approach God and each other with unveiled, shining faces.

In 2 Corinthians, Paul flips the meaning of the Exodus passage on its head but points to the same hardness of heart. In Paul’s reading of the text, Moses decided to wear the veil to obscure the fading of the luminescence (2 Corinthians 3:13). Aside from the differing reasons for veiling, Paul points out that Christians need not veil their faces from God or each other because God-through-Christ has thrust our sins so far from us that we enter God’s presence with absolute boldness (3:12).

This boldness to be in God’s presence without shame or fear reminds me of the situation in the Garden of Eden before the knowledge of good and evil brought about sinfulness. Indeed, the classical work of Jewish mysticism, the Zohar, uses the story of Moses’ face shining and a set of homophones to make a point about what it’s like for humans to be in God’s presence. The Zohar says that in the beginning humans were naked, but their outer covering was like garments of light. Human skin was overwhelmingly radiant and our image was that of the God who created us. But after humans sinned, God took away our garments of light (‘or with an aleph as the first letter) and gave us garments of skin (‘or with an ayin as the first letter) (Genesis 3:21). These weren’t leather garments like the Flintstones wear but our actual skin, which is beautiful and neat, but obscures the inner light we all possess as beloved children of God (Zohar, 2nd edition). So Moses’ face shone not because he had gained in radiance but because the veneer of human fallenness wore thin and God’s innate image broke through.

At Jesus’ transfiguration, the same radiance shines forth, but in a much more concentrated and powerful way. Contrary to some gnostic writings, Jesus wasn’t just God wearing a skin-suit—he is fully human as much as he is fully divine. But because Jesus is sinless, and thus his relationship with God the Father wasn’t impaired, I have to think his normal state is something like the transfiguration that Peter, James and John saw on the mountain. Even though it is highly figurative language, Revelation says Jesus’ face will be as brilliant as the sun and his skin will look like glowing metal (1:15-16). I wonder if, while Jesus was praying, he just lost concentration for a second, and the magnificent glory of the firstborn of all creation (Colossians 1:15) overwhelmed the dust-covered skin that barely contained it. This image of Jesus speaks to me: the messiah who came to earth to be born humbly, walk around in the dust, party hard with his friends, argue with people, lose his cool sometimes, and be crucified in the most shameful way of all, while barely containing his glory.

What does that mean for us? We have to return to Paul in 2 Corinthians. God made humans radiant and resplendent, but then we obscured God’s glory. Allegiance to Jesus demands that we remove the ways we hide and cover ourselves and the glory of God within us (2 Corinthians 3:18, 4:2). God has done the difficult work in removing the powers of sin and death. All we need to do is be bold as we approach God and each other with unveiled, shining faces.