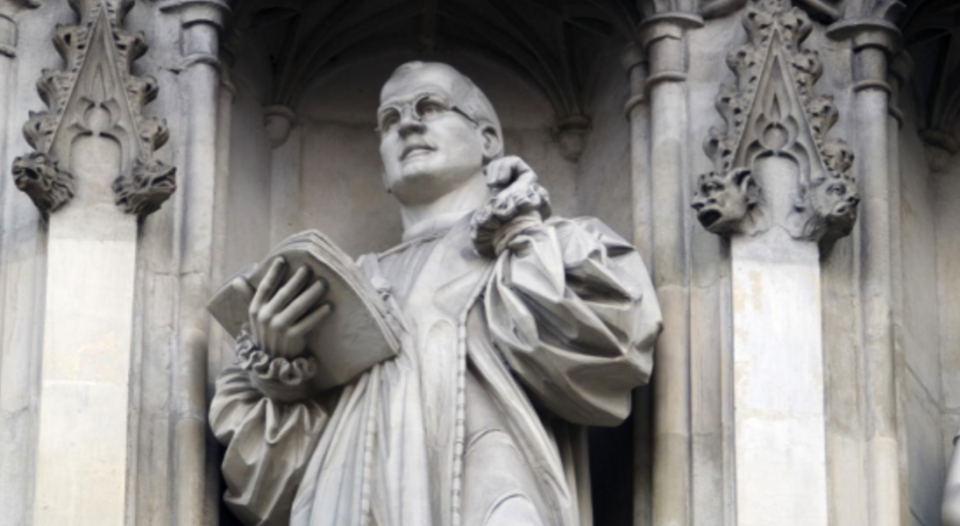

On Monday, April 9, 1945, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was hanged in a concentration camp in Flossenburg, Germany, for his role in a conspiracy to assassinate Adolf Hitler. A week earlier, on April 1, the wider world had celebrated the news that Jesus “is not here; for he has been raised” (Matthew 28:6).

In his death and resurrection, Jesus announced a way of the world far more powerful than those people and things that threaten to undo creation. Neither a world power nor a dreaded illness could begin to loosen the hold God’s love has on the world. Washed in the waters of death and resurrection, fed by Christ’s body, which was broken for the sake of the world, the Christian community stands at the edges in order to look death in the face and proclaim good news. Come what may, “whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord’s” (Romans 14:8).

Bonhoeffer watched violence unfold against a people who had long since been called “chosen”—and those who stood with them. He couldn’t remain silent. He would speak out against genocide in whatever ways he could. When the world fell apart at the seams, Bonhoeffer used his pen and voice to scream good news into its gaping wounds.

When the world fell apart at the seams, Bonhoeffer used his pen and voice to scream good news into its gaping wounds.

Convinced that God most closely identified with those who were beaten, broken and robbed of their livelihoods because of their ethnicity, disability, sexuality or political beliefs, Bonhoeffer set out to write and speak a hopeful word. “Only a suffering God can help,” he wrote in a 1944 letter.

The authorities did everything they could to silence Bonhoeffer, once cutting short a radio broadcast on which he was speaking about the treatment of Jews.

Still, Bonhoeffer continued to speak at the edges, into the deep abyss of death. In his lectures and sermons, the crucified and risen Christ could not be found with those who were powerful and used their power to destroy the lives of millions. Instead, Christ was present exactly when and where all hell broke loose. For Bonhoeffer, Christ stood at the edges, with those who looked into the grave and wondered, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Psalm 22:1).

“I hope to be a Christian”

While directing Finkenwalde, an underground seminary for preachers, Bonhoeffer helped students understand that, through Scripture, God spoke directly to the reader. The reader of Scripture is not alone—God is with them. It is no surprise that, when this seminary was unearthed by the Nazis, it was soon closed.

Bonhoeffer’s voice echoed from the edges in other ways as well. He was a prolific letter writer. Whether he was in New York at Union Seminary or in a pastorate in London or in a concentration camp, his letters reached out to family, to friends but also to those who needed to hear a word of hope amid the world’s chaos.

In Bonhoeffer’s poetry, the themes of God’s presence and of God’s work in Christ for the sake of the world are interlaced with the reality of life in a world come undone. The subversiveness of his poetry may not be obvious. Yet, as Lutheran theologian Vítor Westhelle reminds us, poets name things to which others—including theologians—can only point.

“Whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord’s” (Romans 14:8).

In the myriad genres in which Bonhoeffer put pen to paper, even after his voice was silenced inside the walls of concentration camps, the hope of Christ’s presence and work stands firm.

Some may commemorate Bonhoeffer as a saint, martyr or hero. Yet in a letter composed late in his life, he wrote simply, “I hope to be a Christian.”

Shortly before Bonhoeffer was executed, he wrote: “This is the end—for me, the beginning of life.” Facing powers that would defy the good news of Jesus Christ, that would separate him from God, confound him and drive him to despair, Bonhoeffer used his pen to write a different ending. As a pastor and theologian, he may have proclaimed the good news at the edges of peoples’ lives, but when it came to his own life, he could only fall freely into the grace of God.

The most important question for Bonhoeffer was: “Who is Jesus Christ for us today?” The answer, finally, has to do with what happens when we reach an end. Christ brings us to the edges of resurrection.

Selected works of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

- Discipleship: Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, Volume 4 (Fortress, 2003).

- Life Together and Prayerbook of the Bible: Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, Volume 5 (Fortress, 2004).

- Ethics: Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, Volume 6 (Fortress, 2006).

- Fiction From Tegel Prison: Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, Volume 7 (Fortress, 2010).

- Letters and Papers From Prison: Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, Volume 8 (Fortress, 2010).