Series editor’s note: The 2026 theme for “Deeper understandings” is faithful witness in challenging times. This year, various authors will explore what it means for the ELCA, and each of us as Lutherans, to face the headwinds of societal fracture, loneliness and political contention, and to bear witness to the good news of Jesus Christ that forgives, frees and transforms not only us individually but the whole world. We hope you will be encouraged and empowered to plant your feet firmly on the rock of our faith and speak joyfully and hopefully about the power of the gospel to foster peace and justice in a world desperately in need of both.

—Kristin Johnston Largen, president of Wartburg Theological Seminary, Dubuque, Iowa, on behalf of the ELCA’s seminaries

When we hear the phrase “bearing witness,” two things may come to mind: the positive sense of bearing witness to the gospel and the (negative) prohibition against bearing false witness against one’s neighbor. For Lutherans—who claim a gospel message that frees us not only to worship God but also to serve our neighbor—it is worth asking: what might the one have to do with the other?

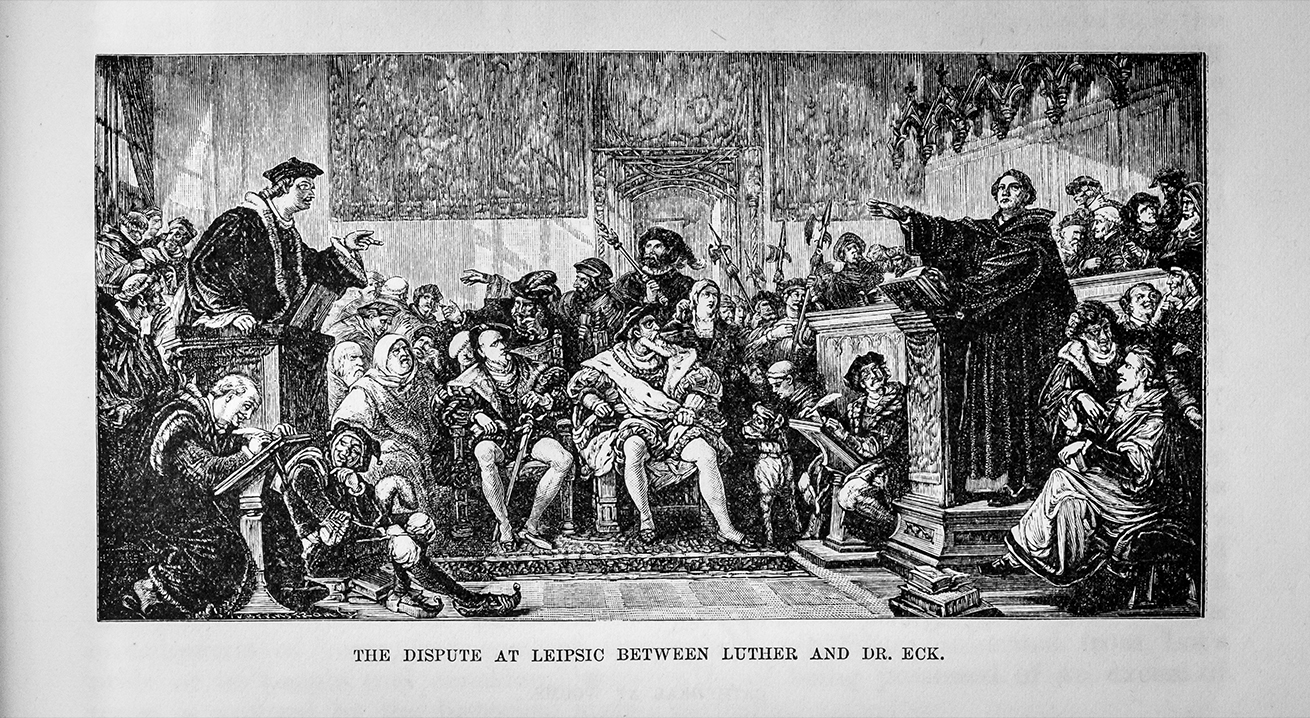

In the Heidelberg Disputation, Martin Luther declares: “A theology of glory calls evil good and good evil. A theology of the cross calls the thing what it actually is.” Luther was troubled by theologies of glory that, in his view, perpetuated structures of power at the expense (monetary and spiritual) of the Christian faithful. Turning prevailing theological assumptions on their heads, he insisted that God should be sought—and would be found!—in the very life spaces where suffering, sin, despair and doubt circulate. To bear witness to the gospel is to seek and declare God’s presence among us, especially amid the very muck of life we mostly prefer to avoid or deny.

This central theological claim from Luther also translates into a broader theological orientation for Lutheranism: ours is an unflinchingly honest theology that does not shy away from the realities of what is. Among other things, this means naming sin and injustice where we see it, especially when these are covered in a shiny veneer. Dazzled and distracted by our electronic devices, we are called to acknowledge the horrific labor conditions that make them possible. Stirred by proclamations of patriotism, which originated as a shared civic value, we are called to denounce when “patriotism” is deployed as a civic weapon and used to justify dehumanizing violence.

If an honest theology questions shiny veneers covering rotten cores, it stands to reason that it should also expose false stories that seek to impugn or oversimplify. While such behaviors are not new to human nature, bearing false witness quickly and on a massive scale requires almost no effort thanks to the digital technologies at our fingertips 24/7.

In fact, looking around, bearing false witness against others seems to be the order of the day, something to be reveled in. These days it is hard to avoid loud accusations against people who do not look or sound like “us”—accusations that do not stop at speech but ultimately fuel a wide spectrum of violence that threatens the safety, health and integrity of entire classes of people. Meanwhile, within seemingly homogenous communities, including churches and even families, political vitriol and rage-baiting reduce the neighbor to a single political identity. In neither case is the neighbor recognized as a complex person who, yes, is flawed but also is a beloved child of God with complex perspectives, emotions and motivations—not to mention someone deserving of dignity and respect.

True witness

In a 2009 TED Talk, author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie unfolds what she calls “the danger of a single story,” that is, the story—always skewed and reductive—that is told about people from a particular place (e.g., Africa, Mexico or England). How is a single story created? Well, Adichie says all one must do is “show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become.” She goes on to point out that power determines the single story: how the story is told, who tells it and who benefits from such a telling (rarely, of course, the people about whom the story is told).

A frequently cranky Bible professor from 16th-century northern Germany and a best-selling contemporary novelist from Nigeria, Luther and Adichie might seem strange bedfellows. Both, however, have something to teach us about bearing true witness to our neighbor, especially when prevailing powers would prefer that we do otherwise. When we call a thing what it really is and resist the temptation of a single story, we not only bear true witness to our neighbor but might even stretch our understanding of who our neighbor is.

If God meets us in our imperfection and, without conditions, claims us as beloved, what could that mean for the conditions we often place on “neighborliness” these days? What steps could we take to loosen those conditions, to deepen the stories we tell—to bear true witness?

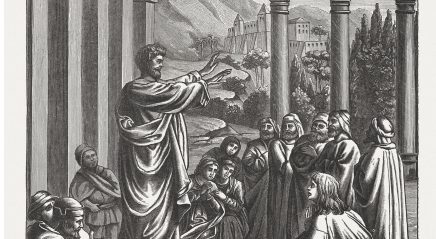

Bearing witness is more than simply witnessing, though it does include that. It first involves seeing: genuinely observing and taking notice of the details rather than reducing matters to platitudes or people to stereotypes. Beyond taking careful notice, bearing witness involves speaking truthfully and clearly, naming things for what they are, no matter how uncomfortable. Finally, if we are genuinely responding to the gospel, bearing witness involves our bodies and all the uniquely human faculties with which God has blessed us.

Translated into bumper-sticker speak, bearing true witness might read: Get curious. Speak truthfully. Act boldly.

As I write these words, Buddhist monks are walking from Fort Worth, Texas, to Washington, D.C., and in a few days will come near my South Carolina town. They are walking for peace, bearing true witness to one of their tradition’s core tenets. How might we, in the coming year, use our mouths and our minds, our hands and our feet, to bear true witness—always within the light of God’s amazing grace?

Get this column in your inbox: Visit livinglutheran.org/create-account and sign up for the free email digest LL Stories. Receive the digest weekly, biweekly or monthly, and select the categories that interest you. (“Deeper understandings” is a “Theology & Beliefs” column.)